– The meaning of Matthew 24:28 according to the ancients

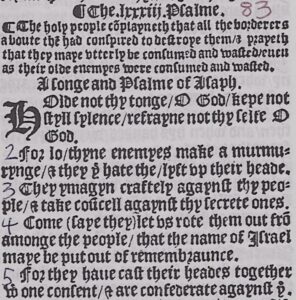

– Back in time: About emblems and emblem books

– The emblem painting of Matthew 24:28

– Further back in time: What Chrysostom, Cranmer, and Jewel said

Matthew 24:28 a call to Holy Communion? So said the ancients.

What does Matthew 24:28 mean? Who are the eagles, and who or what does the dead body represent? See the verse:

For as the lightning comes out of the east and shines to the west, so will the coming of the Son of man be. For wherever the dead body is, there will the eagles resort.

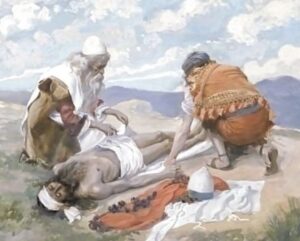

It will seem strange to people nowadays, but for many centuries it was taught in the church that the eagles represent believers, while the dead body represents the body of our Lord, wounded and dead on the cross for us. According to this interpretation, verse 28 is a call to, and a picture of, Holy Communion: the eagles, or believers, soar in flights of faith when they gather at Holy Communion to remember the Body and Blood of the Lord, the crucified Christ. Therefore, as verse 26 says, these eagles do not go out to the desert to find Christ, nor to secret places. Nor do they flock to places where false prophets are working their miracles, as it is said. No, but they go to where he is openly shown in Holy Communion, which is the sacrament and remembrance that he ordained, the Sacrament of his Body and Blood. This is where he is shown and known.

Here are the verses in fuller context:

Matthew 24:23-28, New Matthew Bible: 23Then if anyone says to you, See, here is Christ! or, There is Christ! – believe it not. 24For false christs and false prophets will arise, and will do great miracles and wonders, insomuch that, if it were possible, the very elect should be deceived. 25Take heed, I have told you beforehand. 26So if they say to you, Behold, he is in the desert! go not forth; or, Behold, he is in the secret places! believe it not. 27For as the lightning comes out of the east and shines to the west, so will the coming of the Son of man be. 28For wherever the dead body is, there will the eagles resort.

In partaking of Holy Communion, the eagles find and commune with their Lord; there they remember his atoning death, look upon his saving wounds, and receive of his Body and Blood. There they, as priests of the New Covenant, partake of the altar and are nourished up to holiness and eternal life in the body. And as lightning shines from the east to the west, illuminating all upon whom it lights, so comes the Son of man by the Spirit in his fashion, from the east to the west, wherever the body is shown. I recently heard a bishop put it well: The Eucharist is the presence of the Lord in this world.

The idea that the meaning of Matthew 24:28 concerns the Eucharist (or Holy Communion, the Table of the Lord, etc.) may seem strange, because this teaching is now lost and forgotten. Moreover, if we read modern Bibles, we could never understand Matthew 24:28 as a call to Holy Communion because they use unfitting terms. Some refer not to eagles, but to “carrion vultures,” which is pejorative imagery. The Message Bible by Eugene Peterson even refers to a “rotting carcass” where these vultures gather, rather than simply to a dead body. Since the New Testament expressly says that Jesus’ dead body did not see corruption (Acts 2:27, 2:31, 13:35), there is no way Peterson’s rendering could lead the mind to the holy mysteries: there could be no holy gathering at a sacrament of the “rotting carcass” of the Lord.

I believe modern Bible translators are misled by the word “carcass,” which was used in older Bibles to refer to the dead body of the Lord. Formerly, “carcass” was a neutral term, whereas now it also is pejorative. But I won’t discuss here how modern translations have changed the meaning and tone of Matthew 24:28 because I already reviewed the changes in my 2013 paper here on Academia.edu (linked again at the end of this paper).

I am writing about this topic now again, a decade later, because I recently received an email from a Danish minister, Pastor Poul Asger Beck, after he read my 2013 paper. He told me that there is an old colour painting on the wall of his church, called an emblem painting (shown later), which pictorially links Matthew 24:28 to Holy Communion. Pastor Beck was doing research relating to this painting in connection with a book he has written (1), and that was how he found my paper. He kindly sent some materials to me, and I am excited to share them here.

About emblems and emblem books

I had never heard of emblems or emblem paintings before. Now I know that emblems are allegorical paintings or sketches. As well as emblem paintings that hang on the walls of churches, there are also emblem books. These books are collections of emblems together with explanatory texts, typically morals or poems. Emblem books were popular in the 16th and 17th centuries for devotions and meditations.

Although emblems are, to the best of my knowledge, little known in Canada or the USA, they were widely known throughout Europe. They were apparently the highest fashion for church decoration around the 18th century under Pietism. (Pietism began as a 17th century movement in the German Lutheran Church. Its purpose was to infuse new life into dry Protestantism. It spread to other countries, but took different forms over time.)

Pastor Beck told me that there are emblem paintings hanging on the walls of about sixty churches in Denmark, and they can still be found in churches in other European countries. The cover of his new book (below) features images of several such emblems:

Emblems that answer the question, What Does Matthew 24:28 Mean?

Shown below now is the colourful emblem painting that hangs on the wall of Pastor Beck’s church, and which relates to Matthew 24:28. It was painted in 1705 by Christen Pedersen Lyngbye (1645-1715), who in turn was inspired by the emblem work of a man named Daniel Cramer. The Latin words Sic Alor, writ large in the sky of the painting, mean “Here I feed,” or “So I feed”:

Late 17th or early 18th century painting by Christen Lyngbye, illustrating Matthew 24:28.

Lyngbye’s painting shows a believer as an eagle with a heart-shaped body. To me, this signifies a believer’s love for the Lord, and also that his or her “flight” in Holy Communion is a spiritual one, where heart and soul ascend in faith. The eagle-believer, in remembrance, looks in his mind’s eye upon the Lord’s dead body, which is shown as a pierced hand, foot, and heart, representing the spiritual food of Holy Communion. This is why it is called the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of the Lord.

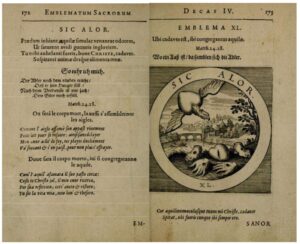

The next item Pastor Beck sent me is the image, shown below, of pages 172-173 from an emblem book called Emblemata Sacra, (or Emblematum Sacrorum) by the aforementioned Daniel Cramer (1568-1637). Cramer himself illustrated the book. He has been identified as a German Lutheran. Some say he had ties with the Rosicrucian movement; I do not know if this is true, but it does not matter since he was only illustrating an interpretation of Matthew 24:28 that long predated him.

Cramer’s emblem again shows the heart-eagle and the Lord’s pierced hands, feet, and heart. A common denominator of Cramer’s emblems was this mystic heart, represented in different situations as soaring on wings, or chained, or nailed to a cross, etc. The words Sic Alor (“Here I feed”) are again seen here, printed prominently above the emblem:

Pages from the 17th century emblem book of Daniel Cramer, with his emblem illustrating the meaning of Matthew 24:28.

The large-print French verse on the page facing Cramer’s emblem says “Où sera le corps mort, là aussi s’assembleront les aigles.” In English this is, “Where the dead body is, there also will the eagles gather.”

Below this, another line in the old French poetry says, “Mon cœur ailé de foi, tes plaies doucement va succant et s’en paist, pour non plus s’effrayer” (partially updated). I tentatively translate this, “My heart, on wings of faith, goes to gently suck and feed upon your wounds, no more to fear.”

Daniel Cramer got his inspiration for this emblem from the ancients. To go further back in time, to see the ancient sources he drew from, below are a few short quotations from leading men of the church.

John Chrysostom on the meaning of Matthew 24:28

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (c. 347-407) was a noted early Church father, known for liturgical reforms in the Greek Church, especially relating to Holy Communion. He was made Archbishop of Constantinople in about 397 AD. He spoke, taught, preached, and wrote in Greek, and studied the New Testament scriptures in their original tongue.

Chrysostom clearly referred Matthew 24:28 to Holy Communion; that is, to our Lord who was slain for us to take away our sins, and to believers at the Communion Table, who, as soaring eagles, remember his death. Chrysostom wrote very eloquently:

For it is to this that the fearful and tremendous sacrifice leads us, warning us above all things to approach it with one mind and fervent love, and thereby become as eagles, so to mount up to the very heaven – nay, even beyond the heaven. “For wheresoever the carcase is,” saith he, “there also will be the eagles,” (Mat.xxiv.28), calling his body a “carcase” by reason of his death. For if he had not fallen, we would not have risen again. But he calls us eagles, implying that the person who draws near to this Body must be on high, and have nothing in common with the earth, nor wind himself downwards and creep along; but he must ever be soaring heavenwards, and look on the Sun of Righteousness, and have the eye of his mind quick-sighted. For eagles, not daws, have a right to this Table. (2)

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a foremost English Reformer. As Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII and Edward VI, he gave the Reformation Church of England her heavenly liturgy for Holy Communion in the Book of Common Prayer. Cranmer was a martyr for the faith, burned alive by Bloody Queen Mary in 1556.

Archbishop Cranmer often quoted from Chrysostom, including where he touched on the meaning of Matthew 24:28 in his homily, The Worthy Receiving of the Sacrament:

Thou must carefully search out and understand what good things are provided for thy soul, whither thou art come [to Holy Communion] – not to feed thy senses and belly to corruption, but thy inward man to immortality and life; nor to consider the earthly creatures [the bread and wine] which thou seest, but the heavenly graces which thy faith beholdeth. For this table is not, saith Chrysostom, for chattering jayes, but for eagles, who fly there where the dead body lies. (3)

Again we see this emphasis upon a true, earnest flight of faith, to appreciate the Lord’s self-offering upon the cross for his eagles.

John Jewel

Bishop John Jewel of the early Reformation Church of England also referred to the high flight of eagle-believers who partake of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of the Lord. He wrote:

For Christ himself altogether is so offered and given us in these mysteries that we may certainly know we be flesh of his flesh and bone of his bones, and that Christ continueth in us and we in him. And therefore, in celebrating these mysteries, the people are to good purpose exhorted, before they come to receive the Holy Communion, to lift up their hearts and to direct their minds to heavenward; because he is there by whom we must be full fed and live. Cyril saith, when we come to receive these mysteries, all gross imaginations must quite be banished. The Council of Nicea, as it is alleged by some in Greek, plainly forbiddeth us to be basely affectioned or bent toward the bread and wine which are set before us. And, as Chrysostom very aptly writeth, we say that “the body of Christ is the dead [body], and we ourselves must be the eagles”: meaning thereby that we must fly on high if we will come unto the body of Christ.” (4)

Conclusion

The ancient understanding of the meaning of Matthew 24:28 was meaningful and reverent, and it saddens me that it has been lost. I myself, since I first learned about it so many years ago, consciously practice this ascent of the eagles when I approach the holy sacrament.

To make an aside, I noticed when I was working on the New Testament that the parallel eagle-and-dead-body passage in Luke 17:37 is not apparently adaptable to the same interpretation. This is the only difficulty with it of which I am aware. Chrysostom and Cranmer did not, that I have ever seen, link the Luke passage with Holy Communion. But whatever the explanation (I won’t speculate here), I know that they were more advanced than I in their understanding. Further, they were uniquely chosen and gifted by God to give us the liturgy of the sacrament. Therefore, even if my heart was not instinctively drawn to their teaching on Matthew 24:28, I would defer to them. They knew the Scriptures. And they taught seriously and thoughtfully about the sacrament, and knew its blessings.

To close with a little more fruit from Cranmer’s pen:

We must be sure we understand that in the Supper of the Lord there is no vain ceremony. It is not just a bare sign. It is not an empty figure of something that is absent. As Scripture says, it is the Table of the Lord, the Bread and Cup of the Lord, the memory of Christ, the annunciation of his death, and the Communion of the Body and Blood of the Lord, in a marvellous embodiment and realization which, by the operation of the Holy Ghost, is wrought through faith in the souls of the faithful. By it not only do their souls live to eternal life, but they trust confidently to gain for their bodies a resurrection to immortality.

This result, and the union which is between the body and the Head (that is, the true believers and Christ), the ancient catholic fathers both experienced themselves and commended to their people. Some of them were not afraid to call this Supper the “salve of immortality” and “sovereign preservative against death.” Others called it a “deifical Communion” – that is, a communion that makes us to be holy like God. Others called it the sweet food of the Saviour, and the pledge of eternal health; also the defence of the faith, the hope of the resurrection; others still, the food of immortality, the healthful grace and conservation for eternal life…

All these things both the Holy Scripture and godly men have correctly attributed to this celestial banquet and feast…Here the faithful may see, hear, and know the mercies of God sealed, Christ’s satisfaction for us confirmed, the remission of sin established. Here they may experience the tranquillity of conscience, the increase of faith, the strengthening of hope, the spreading abroad of brotherly kindness, with many other sundry graces of God. (5)

Amen and amen.

* * * *

Ruth Magnusson Davis, March 2023

For more history from a different perspective, including an etymological study of “carcass” as it was used in older Bibles, my 2013 research paper is here on Academia.edu.

This ancient understanding of Matthew 24:28 is not the only interpretation that has been lost today. Another is the correct understanding of “Christ was made sin for us.” This is a Hebrew idiom which is not understood today. The meaning is that Christ was made a sin offering for us, as Augustine, William Tyndale, John Rogers, and other learned men have explained. I blogged on this topic here.

Another lost understanding concerns the-prohecy-of-daniel-927/

_____________________________________

(1) The book Pastor Poul Beck has written is called (English translation) Riddles of the Heart: The Emblems in Vroue Church Described and Illustrated. It is due to be published in May 2023. It includes colour photos and descriptions of the Vroue church’s forty-one emblems, and the emblems from Daniel Cramer’s Emblemata Sacra with the accompanying poems and biblical texts.

(2) Chrysostom, St. John, Homily XXIV on 1 Cor.x.13, Homilies on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Corinthians. Translator not identified. Editor Paul A. Boer, Sr. Original publisher Wm. B. Erdmanns Publishing Company, date not provided, (Facsimile publisher Veritas Splendor Publications, 2012), p. 266. [English minimally updated.]

(3) Cranmer, Thomas, “The Worthy Receiving of the Sacrament,” contained in Homilies (first published 1547, republished Oxford City Press, 2010), p. 368. William Tyndale called Cranmer “a holy man.”

(4) Jewel, John, An Apology of the Church of England, c. 1561, Editor John E. Booty (First published 1963, republished by Church Publishing Incorporated, New York, 2010), pp. 34-35.

(5) Cranmer, Thomas, excerpts from his homilies on common prayer and the sacraments, updated and published here: Thomas-Cranmer-on-Common-Prayer-and-the-Sacraments. See page 6. The updated homily is the joint work of editors Rev. Stanley F. Sinclair and this author.

Key words: What does Matthew 24:28 mean? The meaning of Matthew 24:28

After the judge has chosen the truest witness, he will say, “When there is a conflict between witness testimonies, I accept the evidence of Witness X.” He does not expect perfection, but will give Witness X the benefit of the doubt. The necessity and wisdom of this approach is obvious. He has to make a decision, get on with his work, and close the case.

After the judge has chosen the truest witness, he will say, “When there is a conflict between witness testimonies, I accept the evidence of Witness X.” He does not expect perfection, but will give Witness X the benefit of the doubt. The necessity and wisdom of this approach is obvious. He has to make a decision, get on with his work, and close the case.