It takes practice, but it is not difficult to learn how to read Early Modern English (EME). And it is worthwhile to learn, because then we can read and enjoy the 1537 Matthew Bible.

Some people who own Hendrickson’s facsimile of the Matthew Bible (the beautiful one with the red cloth cover) say they have given up trying to read it. And truly, when we see the EME text for the first time, it looks like another language. However, once the Matthew Bible opens up to you – especially the Old Testament, which is a masterpiece of clarity – you will not want to read another version. Well, perhaps Myles Coverdale’s Bible of 1535, which I also love, or the Great Bible of 1539-1540. But for these Bibles we also need to know how to read Early Modern English.

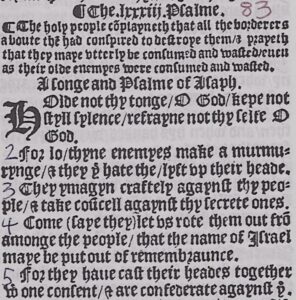

The ten rules below address common features of EME that may cause difficulty to new readers. The pictures of EME text are from the book of psalms in my own copy of Hendrickson’s 1537 Matthew Bible. The psalms of the Matthew Bible were translated by Myles Coverdale, so the word choice and grammar were his, except for the introductory summaries, which were written by John Rogers. However, it was the printer and typesetters who were responsible for page layout and orthography.

What is orthography?

Orthography means a system of spelling and notation. Though the orthography of the early English Bibles seems very inconsistent to us, the typesetters followed certain, definite systems and practices that are easy to learn. Some of their apparent inconsistencies were space-management devices — forms of shorthand, as it were, used only where needed. Because the rag paper used by early printers was thick and the Bible is a long book, typesetters sometimes abbreviated words to shorten the text. On the other hand, sometimes they spelled a word out in full to justify the margins or simply if they did not need to save space.

Knowing the tricks of the printers’ trade as well as a few obsolete rules of grammar will give people a head start in learning how to read Early Modern English texts. I will refer frequently to the specimen text below, Psalm 83:1-5. This specimen includes the psalm title and Rogers’ introductory summary. In modern orthography the summary reads, “The holy people complaineth that all the borderers about them had conspired to destroy them, and prayeth that they may utterly be consumed and wasted, even as their old enemies were consumed and wasted.” Below I explain some of the rules the typesetters followed for the summary and the rest of the psalm:

Psalm 83:1-5 in the 1537 Matthew Bible, with John Rogers’ introductory summary

Ten rules of EME orthography and grammar

1. The symbol below, called a capitulum, was used to indicate a new section. However, it has no other meaning or significance.

![]() A new section in the Bible might be a new book, chapter, or psalm. Also, capitulums were always inserted before Rogers’ introductory summaries, as above in Psalm 83. Perhaps this assisted to show that the summary was added to the biblical text. Because the capitulum served no necessary purpose, it eventually fell out of use.

A new section in the Bible might be a new book, chapter, or psalm. Also, capitulums were always inserted before Rogers’ introductory summaries, as above in Psalm 83. Perhaps this assisted to show that the summary was added to the biblical text. Because the capitulum served no necessary purpose, it eventually fell out of use.

2. Instead of a comma the 1537 Matthew Bible used a mark called a virgule suspensiva, which looks like a forward slash (/). But sometimes a virgule suspensiva was used for a stronger pause, where now we would use a semi-colon or even a period or exclamation mark.

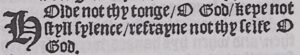

There are virgule suspensivas in every specimen of EME text in this article. If we update verse 1 of Psalm 83, it might read, “Hold not thy tongue, O God! Keep not still silence, refrain not thyself O God”:

Psalm 83:1

3. An old-fashioned form of ampersand (&) was used for the word and. Frequently it was used in combination with the virgule suspensiva (/&).

![]()

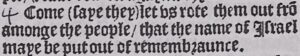

![]() We see the /& combination in the introductory summary of Psalm 83 and in verses 2 and 5. However, and was also spelled out in full in the summary (“consumed and wasted”), and again in the psalm title where it was not necessary to save space (“A songe and psalme of Asaph”).

We see the /& combination in the introductory summary of Psalm 83 and in verses 2 and 5. However, and was also spelled out in full in the summary (“consumed and wasted”), and again in the psalm title where it was not necessary to save space (“A songe and psalme of Asaph”).

With modern spelling and punctuation, verse 2 reads, “For lo, thine enemies make a murmuring, and they that hate thee, lift up their head”:

Psalm 83:2

4. A line over the top of a vowel means that an M or N was dropped (mā = man, becōmeth = becommeth ). Also, special rules for from.

The lines above vowels that marked a missing M or N were called diacritics. Sometimes these diacritics were wavy. There are several in Psalm 83 above. In Rogers’ introductory summary, cōplayneth = complaineth, and in verse 3, coūcell = counsel. Dropping letters allowed the typesetters to justify the margins, or to avoid extending a sentence into the next line in order to save space.

In the first line of Psalm 83:4, shown below, dropping the M in from (frō) clearly helped fit the text into one line. If the typesetters had needed yet more room, they could also have shortened them to thē:

Psalm 83:4

______________

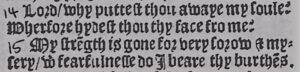

In some places, however, it appears that a diacritic was forgotten, as in Psalm 88 below. Should fro have been written frō in verse 14, “Wherefore hydest thou thy face fro me”?

Psalm 88:14-15

I do not believe “fro me” was a typesetting error in verse 14. For one thing, space did not require that the M be omitted. Also, the term “fro me” without a diacritic was repeated elsewhere. The Oxford English Dictionary shows that from Old English into the Early Modern Period the word fro was sometimes used for from. (Even today fro = from in the phrase “to and fro.”) It seems, therefore, that “fro me” was a special word pair. In EME certain word pairs received special treatment: “shall be” was written “shalbe” and “will be” became “wilbe.” Therefore, from appears to have its own rules: (1) it may be written in full; (2) it may be shorted to frō where needed; (3) in combination with me, it is written fro me.

Turning to verse 15 of Psalm 88, it shows how diacritical notation kept the verse to two lines instead of three. Written out in full, it says, “My strength is gone for very sorrow and misery, with fearfulness do I bear thy burdens.” This verse also manifests other features of EME. One is the frequent use of Y for I (mysery = misery). Another is the use of TH where now we use a D: burthens = burdens (or murther = murder). Also, the special form of the word with near the beginning of the second line in verse 15 was frequently used to save space, which brings us to the next rule.

5. The word with was abbreviated by printing a W with a tiny letter (T or H) above. The words that, the, thee were abbreviated by a Y with a tiny T or E above.

These were space-saving devices inherited from medieval times, when with was written wth and that was written yt. Thee and the were both written ye, and the proper sense was derived from the context.

In Psalm 83:5, wth at the beginning of the second line and ye at the end were used to shorten the words with and thee. This kept the text to one line. In modern orthography this verse reads, “For they have cast their heads together with one consent, and are confederate against thee”:

Psalm 83:5

In verse 2 of Psalm 83, shown below, the Y-form stood for that. As we have seen, in modern orthography this line reads, “and they that hate thee, lift up their head”:

Psalm 83:2

But notice above that thee is spelt the. This takes us to Rule 6.

6. The one-E rule: In the 1537 Matthew Bible the words the and thee were both spelt with only one E (the). Generally speaking, words with an EE sound followed the one-E rule (fre = free, se = see, whele = wheel, seke = seek, etc.).

In Psalm 83:2, which we saw just above, “they that hate the” = they that hate thee.

This spelling of thee seems strange to us, but it was perfectly consistent with the spelling of other English pronouns, such as me (which sounds like mee), ye (yee), and he (hee). Consistent spelling meant that the “rhyme” of Psalm 86:7 appealed to both eye and ear:

Psalm 86:7

In modern orthography, this is, “In the time of my trouble I call upon thee, for thou hearest me.”

However, not all EME texts followed the one-E rule as consistently as the 1537 Matthew Bible did. In other early 16th-century works I have noticed that the and thee were inconsistently spelt, and sometimes reversed.

________________

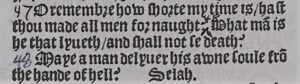

The single E to indicate the EE sound was mirrored also in other words, such as se. Psalm 89:47 reads, “What mā is he that lyveth, and shall not se death?” Here se = see:

Psalm 89:47-48

However, in Psalm 93:5 see = sea in “The waves of the see are mighty, and rage horribly [etc]”:

Psalm 93:5

Thus the apparently odd spellings of thee and see actually manifest consistency in the 1537 Matthew Bible, while they reveal a modern inconsistency (me, thee, see, ye, free, be).

7. Three kinds of Ss (called “allographs” of the S grapheme) were used in the 1537 Matthew Bible:

(1) The descending or long S. This allograph is relatively infrequent. If it followed an orthographic rule, I have not been able to determine it, though in the specimen text below (Psalm 88:18) it appears to be a space-saver.

(2) The “normal” S, such as we use now. The rule was to use this allograph only as a capital letter and at the end of a word.

(3) The f-like S, which was the most common. This looks like an f without the stroke on the stem. It was used everywhere the other allographs were not.

A normal S was used at the end of lovers in Psalm 88:18, shown below. (Here lovers means good and close friends.) However, a descending S was used at the end of frinds (friends). In this verse we also see another example of the word pair fro me without a diacritic:

Psalm 88:18

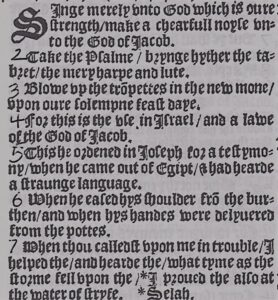

The normal and f-like allographs were used abundantly in Psalm 81 below. The rule for normal Ss (only for capitals and at the end of a word) was consistently followed. Verse 1 reads, “Sing merrily unto God which [who] is our strength, make a cheerful noise unto the God of Jacob”:

Psalm 81:1-7

However, to have three allographs for S was more trouble than it was worth, and by the end of the eighteenth century only the modern form was in use.

8. Past participles of verbs ending in T sometimes dropped the letters ED at the end. (effect = effected, often spelt yfect. Also, the elect = the elected, or the chosen)

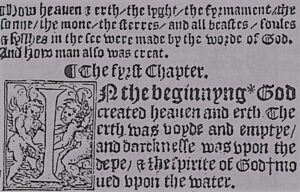

In the introductory summary to Genesis 1 shown below, creat = created at the end of the last sentence. However, midsentence in verse 1 created was written out in full:

Genesis 1, introductory summary and verses 1-2

When a past participle drops the [ed], it is called an absolute participle. Possibly the use of the absolute form was dictated, at least in part, by euphonics. It was more emphatic and pleasing to the ear to end the introductory summary with the stressed syllable (cree-ate). On the other hand, mid-sentence the full form was more rhythmic and pleasing (God cree-ate-ed heav-en and earth).

Some absolute participles remain in use today. The past participle of the verb manifest can be written both ways: it is correct to say both “His real character was manifest by his deeds” and “His real character was manifested by his deeds.” It is the same with the verb incarnate. However, with reference to Christ we speak of him almost exclusively as the Son of God incarnate (= incarnated [i.e., by the Holy Spirit]). I sometimes regret that we do not now speak of Christ incarnated, because the full participle is more meaningful. It clearly conveys the amazing action and event of the Incarnation: the Son of God was born into the flesh of man.

9. The preposition of = by in passive construction.

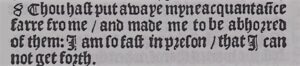

This is an essential rule of grammar for understanding Early Modern English. In the first example below, in modern orthography and putting by for of, it says, “Thou hast put away mine acquaintance [friends] far from me, and made me to be abhorred by them…” (Also, here we see a third fro me word pair):

Psalm 88:8

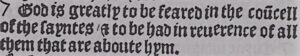

In the next example we would say, “God is greatly to be feared in the council of the saints, and to be had in reverence by all them that are about him.”

Psalm 89:7

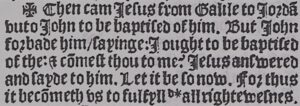

This rule is so important, I will include also an example from the New Testament, speaking of baptism by John or by Jesus:

Matthew 3:13-14

Here we would say, putting by for of in both places: “Then came Jesus from Galilee to Jordan unto John to be baptized by him. But John forbad him, saying, I ought to be baptized by you: and comest thou to me? [etc].”

(Check out how we have gently updated the Gospel of Matthew and other Scriptures for the New Matthew Bible here.)

10. The terms like as and like unto usually just mean like.

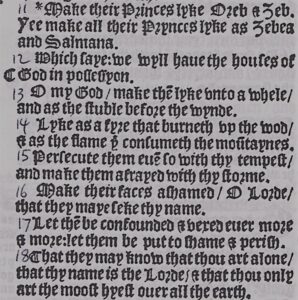

In verses 11-14 of Psalm 83, we find like as, like unto, as, and like all used to express comparison in contexts where the simple word like (or as) could function alone. Coverdale may have used such a variety of expression for interest and poetry’s sake. Notice also the one-E rule followed in whele (= wheel) in verse 13 and seke (= seek) in verse 16:

Psalm 83:11-18

In modern orthography verses 13 and 14 read:

13 O my God, make them like unto a wheel, and as the stubble before the wind.

14 Like as a fire that burneth up the wood, and as the flame that consumeth the mountains.

Gently updating the English, these verses might read:

13 O my God, make them like a wheel, and as the stubble before the wind;

14 Like a fire that burns up the wood, and as the flame that consumes the mountains.

However, the expression like unto had fascinating nuances of meaning. People who enjoy deeper studies of language and grammar might like my article on how William Tyndale used like unto in the Scriptures and in his writing.

****************

With these rules in mind, I hope people will be encouraged to take up their facsimile of the Matthew Bible, practice reading it, and discover how well they can learn to understand it. It took me a little while, but I can now read it as fluently as I read modern text. I know you can too! It is true that the obsolete words will remain a barrier to a full and correct understanding. That is why the Matthew Bible must be updated. However, the spelling and orthography will no longer be an obstacle.

How to read Early Modern English: some words to know:

all way = always

commodity = benefit

fly = flee

lust = wish or desire

other = or

sometime = formerly

syth = since

then = than

wealth = welfare

which = who, with reference to people and to the divine Persons

*************

Copyright claimed by Ruth M Davis, 2021. For permission to republish, recopy, or use contact here. However, limited permission is given for people to print and use this article for personal use with their facsimile of the 1537 Matthew Bible.

KPs How to read Early Modern English; Understanding Early Modern English