“As the bees diligently do gather together sweet flowers, to make by natural craft the sweet honey, so have I done with the principal topics contained in the Bible.” (John Rogers, introduction to the Table of Principal Matters, 1537 Matthew Bible)

This is an introduction to the blog series, Principal Matters from the 1537 Matthew Bible. The purpose of the series is to make people familiar with the Table of Principal Matters in the Matthew Bible and to learn from the English Reformers. It will be a great series for bible study groups to follow topic by topic each month, or for sermon outlines, to preach from the Scriptures.

- What was the Table of Principal Matters?

- What are the topics of the Table?

- Seven foundational points

- A picture of the first page of the Table, including the short, original introduction

What was the Table of Principal Matters?

The Table of Principal Matters was one of the features of the 1537 Matthew Bible that made it the world’s first English study bible. It was a lengthy concordance, set at the beginning of the bible, which reviewed topics of the faith in alphabetical order. Under each topic were short statements of doctrine with verses for further study. A lot of care, thought, and labour went into its preparation.

The Englishman John Rogers compiled and published the Matthew Bible, which was so-called because it was presented to King Henry VIII as translated by “Thomas Matthew.” This was a pseudonym to conceal William Tyndale’s involvement in the translation, because the king had banned all Tyndale’s work. The real translators of the Matthew Bible were William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale. Rogers collated the work of these two men, added over 2,000 expository notes, and then put a church calendar, a review of the age of the earth, other notices, and the Table of Principal Matters, at the beginning of his amazing work.

The Table was not Rogers’ original work, but was taken and translated from the 1535 French bible of Pierre Olivetan.

At our website, NewMatthewBible.org, is information about the Matthew Bible, about our project to update it, and a variety of interesting articles.

What are the topics of the Table of Principal Matters?

Some of the topics reviewed in the Table are Abomination … Abstinence … Adultery … Angels … Anointing … Antichrist … Beatitudes, or Blessedness …… Born Again … Character or Mark (of Antichrist) … The Coming of Christ in the Flesh … The Coming of Christ unto Us … Free Choice or Free Will … Gifts … Hatred … Innocency … Kingdom … The General Judgment … Human Judgment … Providence … Prudence … Tribulation … The Word of God … Wrath or passion of man … Zeal.

This is just a small sampling; the Table had 237 topical entries in all. This series will review most of them, topic by topic, in alphabetical order following the Table. With 1-2 posts per month, it will be good for years to come (God willing). I’ll enhance each study by setting out the bible verses referred to, taken from the Matthew Bible. It is great food for the soul for those who love God’s word.

Seven foundational points

To properly understand the Table of Principal Matters, we need to appreciate that the Matthew Bible is amillennial and non-dispensational.[1] It is therefore premised on the following foundational beliefs concerning the New Covenant and the kingdom of Christ:

(1) Jesus’ kingdom is now; his marvelous kingdom has come. There is no promise of a worldly kingdom yet to come in a future millennium (as many interpret Revelation 20 nowadays). The Lord’s kingdom came in power at Pentecost. It is spiritual and heavenly, in spirit and in truth in the power of the Holy Spirit. In his kingdom, Jesus reigns in the hearts and consciences of his people. Rogers wrote in his note on John 18:36, where Jesus said that his kingdom is not of this world:

That is, my kingdom is not a worldly kingdom, which consists in strength, in armour, in men, in the sword, and in taking dominion over things of this material or worldly realm. But my kingdom is spiritual, and is in the hearts of the faithful, who are ruled not by the sword, but by the gospel.

(2) Under the New Covenant, the “people of God” means all believing people, Jew and Gentile. We are both as one in Christ Jesus because the middle wall of partition has been broken down (Eph. 2:14). There is no longer any difference Jew and Gentile, nor a special, favoured place for Israel:

Now there is neither Jew nor Gentile, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither man nor woman, but you are all one thing in Christ Jesus. (Gal. 3:28)

One of the first Principal Matters topics is “Accepcyon” (that is, “Acception,” an obsolete word meaning “Partiality”). This entry shows how God is not partial to any man or nation, with Scriptures in support from both the Old and New Testaments.

But people may object that, under the Old Testament, the Jews had a special place and special promises. Indeed, but this was by way of example (1 Cor. 10:6,11), and to accomplish his purposes through them, but not out of partiality. For though he set his affection upon them, yet many were overthrown in the wilderness (1Cor. 10:5, Heb. 3:17). Rogers shows under the topic “Abrogation” how it was for its futility that the Old Covenant was abrogated; that is, completely done away with. It is written in Hebrews 7:18, “The previous commandment is abrogated because of its weakness and unprofitableness.”

Paul addressed the question of the preferment of the Jews in Romans 3:

What preferment, then, has the Jew? Or what advantage from circumcision? Surely very much. The word of God was committed first to them. What, then, if some of them did not believe? Does their unbelief make the promise of God without effect? God forbid. Let God be true and all men liars, as it is written: That you may be justified in your words, and should overcome when you are judged…. For we have already established that both Jews and Gentiles are all under sin, as it is written: There is none righteous, no, not one…. Without doubt, the righteousness which is good before God comes by the faith of Jesus Christ, to all and upon all who believe. There is no difference. For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. (Ro. 3:1-4, 9-10, 22-23)

(3) In the Bible, the “last days” (or “latter days”) generally refers to the entire period from Christ’s first to second coming. Rogers clarified this point several times in his expository notes. Many Scriptures support this. Peter said at Pentecost that the pouring out of the Spirit indicated that the last days had then arrived, pursuant to Old Testament prophecies (Acts 2:17). In Hebrews, also written in the first century, we are told that “in these last days” God has spoken to us by his Son. Therefore, the things of the last days are now, and they include not only Christ’s kingdom, but also the kingdom of Antichrist and tribulation. “Tribulation” is one of the topics of the Table that we will see.

(4) I would add my own point (which I have not seen addressed in the notes of the Matthew Bible nor in the Table of Principal Matters), which is that most amillennialists believe the 1,000-year millennium of Revelation 20 is the “last days.” The number 1,000 simply signifies a very long period of time. In the Hebrew tongue, numbers were often used symbolically (as, for example, the number ‘7’ symbolizes fullness or completeness). Another way to put it is, the 1,000 years signify God’s patience.

(5) I would add also that, in Jesus’ kingdom, the first resurrection mentioned in Revelation 20 is the resurrection of the soul when the people of God pass from death to life upon hearing the gospel and believing on Jesus. The second, general resurrection is the raising up of the bodies of all people from their graves, and will take place at the second coming. For believers, who are blessed to have part in the first resurrection (Rev. 20:6), the second resurrection, with union of soul and body and the promise of the entrance into the eternal life, is their hope. However, the hope for a future earthly dispensation when the Jewish nation will be exalted is the hope of Judaism.

(6) When Jesus returns, it will mark the end of his present kingdom in this earth and the end of time. It will bring the judgment, and the new heavens and earth will be ushered in, which will never pass away. Revelation 10:6 in Tyndale’s New Testament says that when Jesus returns, “there should be no longer time”; that is, time will be no more. The KJV has, “there should be time no longer.” In other words, time will not be for one minute longer, let alone a thousand years.

But many modern Bibles changed the translation. In the NIV, Revelation 10:6 reads, “There will be no more delay!” This is ambiguous. It could mean, no more delay till the end of the world. But it obviously (and more easily) supports the hope of a new age during which time will continue.

(7) The Reformers called the belief in a future, utopian, earthly kingdom a “Jewish dotage,” being derived from Judaic doctrine. In the 1553 Articles of Religion of the Church of England, Thomas Cranmer wrote about “Millenarii” (those who believe in a future millennial kingdom):

Heretics called Millenarii: They that go about to renew the fable of heretics, called Millenarii, [are] repugnant to Holy Scripture, and cast themselves headlong into a Jewish dotage.[2]

A gospel that promises another kingdom, one other than the present kingdom of Christ, really is another gospel (2 Cor. 11:4, Gal. 1:6-8). It denigrates from the greatness, reality, power, and wonder of Christ’s reign now – as all “other gospels” will do. It fractures our singular focus on the spiritual kingdom and its promises, to turn our eyes to another kingdom – a political one, so to speak – and to other promises.

When a person becomes familiar with the Matthew Bible, it washes the mind of the taint of strange doctrines. Over the years, many changes have been introduced to the original Scripture translations of William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale. These subtly or overtly contribute to weakening the truth that was purely set forth in the blood-bought Matthew Bible. Many of these are discussed in Part 2 of the Story of the Matthew Bible.

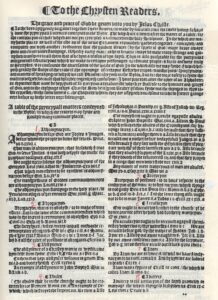

The first page of the Table, including the short, original introduction

Below is an image of the first page of the Table of Principal Matters in the 1537 Matthew Bible, including the introduction “To the Christen Readers.” This is a scan of my Hendrickson facsimile. The red numbers are my own, which I inserted for reference. Rogers also took the introduction from Pierre Olivetan’s 1535 Bible and translated it from the French.

The first page of the Table of Principal Matters in the 1537 Matthew Bible, with the introduction at the top.

Ruth Magnusson Davis, June 2022

________________________

Endnotes:

[1] Issues of the millennium are covered in more detail in chapter 27 of Part 2 of The Story of the Matthew Bible. See also my paper Christian Zionism: Rebuilding Jericho.

[2] Article XLI of the 1553 Articles of Religion was removed in 1563. Both pre- and postmillennialism have roots in Judaism. The concept of a future millennium is tied to a rabbinical interpretation of the creation week. The Jewish belief was that, after the fall, the world would continue for 6,000 years, and then there would be a millennium of rest, or Sabbatical millennium – a kind of earthly utopia. A Christianized form of this doctrine was known in the early Church as chiliasm, from the Greek chiliad or ‘thousand.’ Its adherents were called Chiliasts; they believed Christ would return and reign with the saints on earth for a thousand years. Some well-known Chiliasts were Irenaeus and Tertullian. Chiliasm was identified as a “Jewish fable” and put to rest in the 4th century, but was revived by the Anabaptists during the Reformation.

Dispensationalism began in early 19th-century England. It divides human history into seven dispensations or eras, from the era of innocence before Adam’s fall, through to Christ’s reign in a messianic kingdom during a future seventh and final age. The period from Moses to Jesus is considered the dispensation of Mosaic law.