Did the 1537 Matthew Bible teach that the earth is flat? Or did it teach that the world is round? In fact, both the phrases “flat earth” and “round world” occur in the Matthew Bible (as well as in other early English Bibles). See the following examples from the Old Testament:

2 Samuel 11:11 Uriah said unto David: the ark and Israel and Judah dwell in pavilions, and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord lie in tents upon the flat earth: and should I then go into mine house, to eat and to drink and to lie with my wife?

1 Samuel 2:8 The pillars of the earth are the Lord’s, and he hath set the round world upon them.

Do these verses show that the Bible contradicted itself about the shape of the earth? No, not at all. The Matthew Bible never intended to say that the planet earth is flat, but did say that the world is round, by which was meant round as a globe. This point needs to be made, because the flat-earth movement is growing among Christians, and many believe the falsehood that the early Bibles said the earth is flat.

Here we will see some of the verses that flat-earthers misunderstand, consider the Hebrew, and review what the ancients really believed about the shape of the earth. We will also see an expository note from the Matthew Bible that shows how bible references to the earth standing on pillars must be taken figuratively: the Matthew Bible was no flat-earth Bible!

About Flat-earthers

Recently, a fellow contacted me to share his research proving that the earth is flat. Through simplistic literalism, such as construing the pillars of 1 Samuel 2:8 as literal pillars, he has also concluded that the flat earth is stationary in space, not circling around the sun. Flat-earthers think that the early English Bibles taught these great truths, but the information was removed from later versions “for political reasons.”

But, as will be seen, the reverse is true: it is the truth about the “round world” which was removed from later versions.

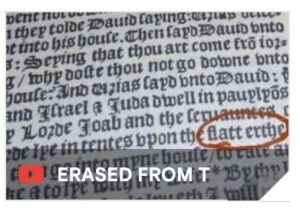

The flat-earther sent me a link to a video talk with the image shown below from a 16th-century printing of 2 Samuel 11:11. The caption, which is not entirely visible, suggests that the circled words (“flatt erthe”) were “erased” from the text in order to conceal the great, now-lost truth that the earth is flat:

Flat-earthers believe in error that the Bible’s teaching about the flat earth was “erased” from early bibles.

The same flat-earther sent me a long meme with a list of Bible verses which, he claimed, support his beliefs:

Terrible bible exegesis to prove that the Bible says the earth is flat.

Experience proves that there can be no discussing the issues with flat-earthers. However, the rest of us should know what the early English Bibles actually said.

Summary of my conclusions

Before discussion, below is a summary of my conclusions:

1. The Matthew Bible did NOT teach that the earth is flat. The phrase “flat earth” in 2 Samuel 11:11 simply refers to the flat ground where Joab and his army were encamped; that is, ground that was flat as opposed to hilly or mountainous. It was not saying that our planet is flat as opposed to round. Many later Bibles put “open fields” here. This was not to hide the truth about the shape of the earth, but was a simple translation.

2. The Matthew Bible gave the full sense of the Hebrew noun tay-bale wherever it used the phrase “round world,” and thus showed that the earth is spherical or globular in shape. According to many authorities, tay-bale implies a spherical shape. (I realize the earth is not a perfect sphere, but is slightly flattened at the poles.)

3. Flat-earthers rely upon false histories (not to mention false science) to buttress their error. They accept a myth that is common among both Christians and non-Christians, whether or not they are flat-earthers, that the ancients believed the world was flat. They also think the Christian Church taught this for centuries, which is another myth. History shows that the Greeks confirmed millennia ago, through astronomical observation, that the world is a spherical orb, and many Christians of antiquity, including Bede and Thomas Aquinas, held to this view. Further, the Oxford English Dictionary shows an Anglo-Saxon quotation from 1300 which says the earth is “round as an apple” (seen below). The idea that the world is round was not new to the translators (or the readers) of the Matthew Bible.

A great discussion of what the ancients really believed is by Jonathan Sarfati in his article “Flat Earth Myth,” linked at the end of this blog post. Mr. Sarfati is a Jewish Christian and a director of the Institute for Creation Research.

The “flat earth” of 2 Samuel 11:11

To understand how “earth” was used in the Matthew Bible, we need to know that in the 16th century, people sometimes said “earth” where now we would say “ground.” See the following example from 1 Samuel 5:3 (note, “Dagon” mentioned in this verse was an idol set up in a pagan temple):

1 Samuel 5:3 And when [the people] of Ashdod were up in the morning, behold, Dagon lay [face-down] upon the earth before the ark of the Lord. And they took Dagon and set him in his place again.

Now we would say, “Dagon was lying face-down on the ground.” In the very next verse, in the same context, Tyndale used the word “ground,” which shows that this was indeed the sense:

1 Samuel 5:4 And when they were up early in the next morning, behold, Dagon lay [face-down] upon the ground before the ark of the Lord.

Below is a further example, this one from 2 Samuel. Here King David had just received news that all his sons were dead (though in fact only Amnon was dead):

2 Samuel 13:31 Then the king arose and tare his garments, and lay along on the earth.

This means, of course, that he lay along on the ground.

The sense “ground” was also the meaning at 2 Samuel 11:11, where the Matthew Bible had “flat earth.” It was describing the terrain where the army of Joab was encamped. The Hebrew word translated “ground” in this verse was saw-deh, which means “spread out,” just as any expanse of flat land appears spread out. See below how much more meaningful the verse is when updated to “ground.” In addition, I updated “flat” to “open,” as other Bibles have here. Also shown for comparison is the KJV rendering:

2 Samuel 11:11

1537 Matthew Bible Uriah said unto David: the ark and Israel and Judah dwell in pavilions: and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord lie in tents upon the flat earth: and should I then go into mine house, to eat and to drink and to lie with my wife?

Update, New Matthew Bible Uriah said to David, The ark and Israel and Judah dwell in temporary shelters, and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord lie in tents on the open ground, and should I then go into my house to eat and drink and lie with my wife?

1611 KJV And Uriah said unto David, The ark, and Israel, and Judah, abide in tents; and my lord Joab, and the servants of my lord, are encamped in the open fields; shall I then go into mine house, to eat and to drink, and to lie with my wife?

The adjective “flat” in verse 11 translates the Hebrew paw-neem, which literally means “face.” Now we would better say “open” because the point was that, as flat land, it was open and unsheltered. Uriah was saying that he would not go to the shelter of his own home while his fellow soldiers lay in tents outside on wide open ground.

But to the chief point, Uriah was certainly not saying in 2 Samuel 11:11 that Joab’s army lay in tents on a flat planet. That would be an irrelevant detail, and ridiculous.

“Round world” in the Matthew Bible and other early English Bibles

Some say the phrase “round world” does not in itself prove anything either for or against the flat-earthers, because both a flat disc and a sphere can be described as “round.” True, but the evidence is convincing that “round world” in the early English Bibles indicated a spherical shape. As mentioned, the English people had for many centuries known that the earth is a sphere, as are also other heavenly bodies. Below, from the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), are three sample quotations from ancient writings:

c1300 Ase an Appel þe eorþe is round. [= As an apple, the earth is round.]

1400 (▸a1325) In þe sune…Es a thing a[nd] thre thinges sere; A bodi rond, and hete and light. [= In the sun…is a thing and three things sure; a body round, and heat and light.]

1475 (▸1392) Heuene ys round in þe maner of a round spere in þe myddis of whiche hangiþ þe erþe. [= Heaven is round in the manner of a round sphere, in the midst of which hangs the earth.][1]

As mentioned, the Mathew Bible was not alone in describing the world as “round.” See the other two Reformation Bibles, Myles Coverdale’s of 1535 and the 1540 Great Bible:

1535 Coverdale, Psalm 18:15 The springs of waters were seen, and the foundations of the round world were discovered [uncovered] at thy chiding (O Lord) – at the blasting and breath of thy displeasure.

1540 Great Bible, Jeremiah 51:15 Yea, even the Lord of hosts, that with his power made the earth – with his wisdom prepared the round world, and with his discretion spread out the heavens.

We might ask, when was the adjective “round” removed from the verses we have seen? The removal first came in the 1560 Geneva Bible revision. I say “revision” because the Geneva Old Testament was not an original translation, but was actually a revision of the Great Bible.[2] Therefore, the editors must have intentionally removed the adjective “round” in the course of their reviews. Where I spot-checked the 1568 Bishops’ Bible, I saw that it had followed the Geneva version, even though the bishops were also working from the Great Bible (or, were supposed to be working from it). Therefore, they also must have intentionally removed “round.” Then the KJV, in its turn, also omitted it everywhere.

And so, it was actually the teaching about the round world that was erased from the Bible. I wonder how the flat-earthers would answer this, if they actually read the old Bibles and discovered the truth?

The Hebrew

In every instance where I found “round world” in the Matthew Bible, it was translating the Hebrew noun tay-bale (Strong’s #8398). Tay-bale is defined as follows in the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (TWOT):

TWOT 835h תֵּבֵל têbêl, tay-bale’; world: First, the noun is employed to represent the global mass called earth, including the atmosphere or heavens (cf. Ps.89:12 [or 89:11]; II Sam 22:16; et al.). … In several passages the sense of têbêl as the globular earth in combination with its inhabitants is clearly observed.

We see that, according to TWOT, the idea that the earth is globe-shaped (“globular”) is implicit in the Hebrew. Strong and Gesenius indicate the same. Therefore, the question is not so much why “round world” is in the early Bibles, but why was it removed? In certain verses, the answer is that the revisers re-interpreted tay-bale to apply it to the inhabitants of the earth, and not to planet earth. (I discuss this in my paper, The Round World in the Matthew Bible, linked at the end.) This is another meaning of tay-bale, as TWOT indicates. However, this does not explain every change.

Perhaps, in those verses that relate to planet earth herself, the revisers did not agree on the meaning of the Hebrew. Some scholars say tay-bale does not indicate anything about the shape of the earth. I corresponded with a modern Hebraist who wrote to me (also mentioning the Latin in his argument),

The fact is, in some passages, TBL [tay-bale] is referring to the inhabitants of the world, and in others, it’s talking about the physical earth. But it’s never talking about the shape of the planet. Orbis or orbis terrarum was a common Latin word or phrase for the whole world. Lexicons explain that the ancients viewed the world as a “circular plane or disc.” The word orbis itself can mean ring or circle. I’ve never seen an indication of it meaning sphere.

However, since this scholar’s opinion, and that of the lexicons he uses, disagrees with other authorities, it cannot be definitive. Further, both he and his lexicons premise their limited definition of tay-bale on the myth that the ancients held to a flat earth. They seem to think that since the ancients believed the world was flat, therefore their language could not have contemplated a spherical earth. But since this premise is false, their conclusion is doubtful, and their definition of the Hebrew could, as a consequence, be incomplete. Furthermore, I have read authorities who say the Latin word orbis may indicate a sphere, contrary to this scholar’s statement. Therefore, I do not have confidence in his opinion.

When it comes to understanding the ancient languages, one must choose thoughtfully who to trust, because there is always disagreement. Further, Satan never rests from his work of confusing, obscuring, suppressing, and changing meanings. In many things, the early Reformers and original translators – William Tyndale, Myles Coverdale, and Martin Luther, whom God raised up to open his word to the world – prove most trustworthy.

As a final example, see Psalm 96:

Psalm 96:10 Tell it out among the heathen, that the Lord is king: and that it is he which [who] hath made the round world so fast, that it cannot be moved.

Concerning this psalm, flat-earthers think that the round world being “unmoveable” means it is stationary in space. They misunderstand the figurative speech, which concerns the stability of God’s creation under his almighty control.

Finally, I note also that the other Hebrew noun in the Old Testament which was sometimes translated “world” “or “earth” is eh-rets (Strong’s #776). Jonathan Sarfati wrote that eh-rets also implies “ball-shaped” (see page 6 of his article “Flat Earth Myth,” linked below). I was also interested to learn from a former Muslim that the Koran says the earth is egg shaped, not flat. However, I have also been informed that Muslim scholars teach that the earth is a sphere. I am no expert on the teachings of the Koran, but in any case, we know that it draws from the Hebrew Old Testament, and Mohammed was informed, at least in some small part, by the Jews of his time. Perhaps they taught him that the Hebrew indicates the world has a spherical shape.

In conclusion, the first English translators, when they spoke of “the round world,” were capturing the full sense of the Hebrew noun tay-bale, in which the sense of roundness is implicit just as it is in our noun “globe.” Further, the knowledge of the shape of the earth was not new to them or to their audience any more than it would have been new to the ancient Israelites who read the Hebrew scriptures. It also makes sense that God’s word should convey this truth.

Therefore, the truth about what the old Bibles said is the opposite of what the flat-earthers claim: it was in fact clear teaching that the world is round which was removed from the Bible. And the irony is that this omission serves their purpose: it renders the Bible silent about the shape of the earth, so that they can then fill the silence with their false “proofs” that the Bible says the earth is flat.

John Rogers’ Expository Note on Heavenly Pillars

The book of Job contains a few references to “pillars” in connection with the earth and heaven. Job 9:6 says that God,

shifts the earth out of her place so that her pillars shake.

Also, verses 4-6 in chapter 38 read (and this is God speaking):

Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? Tell plainly if you have understanding. Who has measured it, know you? Or, who has spread the line upon it? Whereupon stand the pillars of it?

But John Rogers added a note on Job 26 in the Matthew Bible to help readers understand that such references to heavenly “pillars” are and must be purely figurative. Since verse 7 in chapter 26 says that the earth is “hung upon nothing,” therefore, he wrote, the “pillars” of verse 11 (and other bible verses) must be figurative. Here are the verses and Rogers’ expository note, all as updated for the New Matthew Bible:

Job 26:7 He stretches out the north over the empty space and hangs the earth upon nothing.

Job 26:11 The very pillars of heaven tremble and quake at his reproof.

Expository note: Heaven and earth have no literal pillars, nor anything to lean on that would support and bear them up, as it appears of the earth above in verse 7 of this chapter. But Job draws his similitude from our earthly buildings so that his hearers would the sooner understand him.

Therefore, all things considered, it is utterly wrong to say that the Matthew Bible taught a flat earth, or that it supports the position of the flat-earthers. On the contrary, it refutes their position.

Ruth Magnusson Davis, 2023 (update Feb 2024)

* * * * *

A deeper look at the issues, and a comparison with other Bibles to see what they did with some of the other “round world” verses, is in my paper posted on Academia.edu: The “Round World” in the Matthew Bible.

Here is the link to Jonathan Sarfati’s article Flat Earth Myth. In it, he shows what the ancients taught and believed about the shape of the earth.

[1] These quotations are from the online Oxford English Dictionary under “Round, adjective,” definition 2, accessed March 28, 2023. The definition is: “Having the form of a sphere; shaped like a ball, spherical; (also) more or less spherical in shape; globular.” The OED is only accessible to subscribers or through some libraries.

[2] The sources of the Geneva Bible are discussed in Part 2 of The Story of the Matthew Bible. There is also lots of information about other changes that later revisers made to the Bible in both parts 1 and 2 of The Story. The Matthew Bible (MB) formed the base of and was revised for the 1539 Great Bible, and then went on to be overlaid with more and more revisions in the Geneva Bible (GNV), Bishops’ Bible, and King James Version.

KWs Does the Bible teach that the earth is flat? Did the early bibles say that the earth is flat?