One ill-fated day in Geneva, in the autumn of the year 1551, a man named Jerome Bolsec rose up at the conclusion of a religious meeting and objected to the preaching on predestination that he had heard that day. Some historians indicate that this occurred in John Calvin’s own church, however it was another man who delivered the sermon that day. The custom was to allow discussion about the sermon topic after the conclusion of the service.

Bolsec was a French refugee who had settled in Geneva and worked as a physician. However, he rejected Calvin’s doctrine of predestination, and he believed that it is wrong to preach on predestination as was done in Geneva. This day he could tolerate it no more. Apparently he thought Calvin was out of town, but in fact Calvin had just returned from a trip and was sitting at the back of the congregation. As the historian Mosheim put it, “[Bolsec’s] imprudence was great … It led him … to lift up his voice in the full congregation after the conclusion of divine worship…”[1]

The Geneva magistrates arrested Bolsec for his outburst and cast him into prison. Hoping to demonstrate the correctness of their doctrine and the unity of Swiss Protestants, they sent a letter about the Bolsec matter to the ministers at Basel, Zurich, and the canton of Bern. However, the responses were disappointing to Calvin. Doctrinal support was tepid, and the advice was to be lenient with Bolsec.

But the magistrates pursued their course. They charged Bolsec with attacking the religious establishment of Geneva and bringing scurrilous charges against its doctrine. The trial and prosecution proceeded, and on December 23, 1551 – just in time for Christmas – the physician was permanently banished from Geneva.

The gentlemen of Bern wrote that it is unnecessary and inadvisable to preach on predestination

It seems that the Bolsec matter, and the question of whether it is right or wrong to preach predestination, engendered much debate among the Protestant churches. Some time afterward, the ministers of Bern wrote:

There have been various disputes in the canton of Bern on the question of predestination. Many ministers have spoken against Calvin’s view, and accuse him of making God the author of sin. This caused the gentlemen of Geneva to send to Bern, and Calvin was one of the delegates.

But the gentlemen of Bern did not wish to take any part in these disputes. They said simply that they would exhort their ministers to speak with reserve on these matters. And they also exhorted the Genevans to speak but little, and with great circumspection, on the issues raised, like predestination, the knowledge of which is not at all necessary to salvation, and which are not good for anything but engendering doubts; that it is not to man to enquire into the secrets of God; that the more one digs, the more one finds the impenetrable; that they wish neither to affirm nor condemn the writings and doctrine of Calvin, but that they wish to deter people from disputing on these matters in their country.[2]

Following this, an edict was passed in Bern to restrict the preaching of predestination in the churches. [3]

Luther, Cranmer, and Tyndale accepted the truth of predestination, but indicated also that it is not a suitable topic for common preaching

The position of the ministers at Bern was similar to that of Martin Luther, who, though he did affirm predestination, discouraged enquiring into the hidden decrees of God. He urged people simply to cling to the revealed Jesus. Likewise Thomas Cranmer’s 1553 Articles of Religion of the Church of England, published less than two years after the Bolsec affair, said that it is wrong to preach predestination and election to the common people, because to hold these difficult doctrines before their eyes casts them into despair and doubt, and even into sin:

Article XVII. Of Predestination and Election, 1553 Articles of Religion of the Church of England: Predestination to life is the everlasting purpose of God, whereby, before the foundations of the world were laid, he hath constantly decreed by his own judgement, secret to us, to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he hath chosen in Christ …

As the godly consideration of predestination and our election in Christ is full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons, and such as feel in themselves the working of the Spirit of Christ … so for curious and carnal persons lacking the Spirit of Christ, to have continually before their eyes the sentence of God’s predestination is a most dangerous downfall, whereby the devil may thrust them either into desperation, or into a recklessness of most unclean living, no less perilous than desperation.

Furthermore, although the decrees of predestination are unknown to us, we must receive God’s promises in such wise as they be generally set forth to us in holy Scripture, and in our doings that will of God is to be followed which we have expressly declared to us in the Word of God.

Common sense tells us that desperation, disbelief, offence, confusion, and more will be the results of preaching predestination to the masses. This is true especially in a national church such as Calvin’s was, and as was also the Church of England. To such churches a multitude of people from every walk of life came every Sunday – many of whom, according to Calvin’s own doctrine, were not among the elect. Even worse, in Geneva church attendance was compulsory, and many avowed unbelievers were forced grudgingly into the pews. In The Story of the Matthew Bible Part 2 I discuss the case of Jacques Gruet, an unbeliever who was beheaded after pinning a defiant note to Calvin’s pulpit.[4] What gratuitous folly it is to preach to such people that they cannot choose God, and therefore they are going to hell for eternity if they are not among the elect! This only pleases the devil.

The fact is that such preaching does not proclaim the gospel: it will not save a single soul. It will only work against the gospel, because it will cause people to condemn God or the church, and it will work desperation or recklessness, as Cranmer warned in Article 17, and it will engender needless disputes, as the gentlemen of Bern warned. Jerome Bolsec’s unhappy Christmas proves the truth of these things.

As Tyndale said in his prologue to Romans – which he took largely from Luther, and which therefore expresses also Luther’s mind – the question of predestination is for mature Christians only:

In [Romans 9-11] Paul treats of God’s predestination, by which is determined entirely whether we will believe or not believe, be set free from sin or not be set free, and by which our justification and salvation are taken completely out of our hands and put in the hands of God alone. And this is most necessary, because we are so weak and so uncertain. If it depended on us, there would of a truth be no one saved; the devil would surely deceive and overcome us…

But follow the order of this epistle. First, make Christ your study and concern. Learn what the law and the gospel are, and the office of both, so that you may in the one know yourself, that you have of yourself no strength but to sin, and in the other know the grace of Christ. And then see that you fight against sin and the flesh, as the first seven chapters teach you. After that, when you come to the eighth chapter, and are under the cross and suffering of tribulation, the necessity of predestination will be sweet, and you will feel how precious a thing it is.

For unless you have borne the cross of adversity and temptation, and have felt yourself brought to the very brim of desperation, yea and to hell’s gates, you cannot come to grips with the doctrine of predestination. For it will not be possible for you to think that God is righteous and just. Therefore the old Adam must be well mortified, and fleshly reason destroyed, before you can accept and drink such strong wine. Take heed to yourself therefore, not to drink wine while you are yet but a babe. For all learning is progressive, and has its time, measure, and age. In Christ there is a certain childhood in which one must be content with milk for a season, until he or she is stronger and able to eat stronger meat.[5]

If the doctrine of predestination is not for young believers, it is assuredly not for the general congregation. The wise person will be as humble and circumspect as the gentlemen of Bern in approaching such deep mysteries.[6] However, we are commanded to preach freely to all creatures the joyous message of the mercy and grace that is in Christ Jesus our Lord, and that will assuredly please God.

R Magnusson Davis, Christmas 2020

*********

[1] John Lawrence Mosheim, translator Archibald Maclaine, An Ecclesiastical History: Ancient and Modern, from the Birth of Christ, to the Beginning of the Present Century: In Which the Rise, Progress, and Variations of Church Power are Considered… By the Late Learned John Lawrence Mosheim, D.D., 1768. In Five Volumes. Volume IV, p.125 ff.

[2] This is my (Ruth’s) translation from the old French as given in Richard Laurence, An Attempt to Illustrate Those Articles of the Church of England which the Calvinists Improperly Consider as Calvinistical, 4th edition (Oxford: John Henry Parker, 1853), p. 243. For what it is worth, I believe Laurence misunderstands Article 17 of the Articles of Religion, though his historical review is interesting.

[3] Ibid p. 244.

[4] See Appendix E of Story Part 2.

[5] Tyndale’s prologue can be viewed here on the New Matthew Bible Project website.

[6] I have not even attempted to enquire how Calvin differed from Luther and others in the substance of his doctrine. Regardless, the conclusion about whether it is right or wrong to preach on predestination holds true.

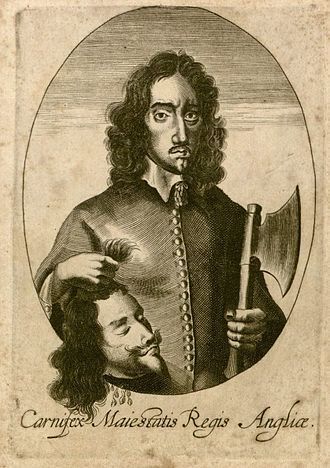

But now, for Part 2 of The Story I have been researching the revolutionary Reformers, who sought from the very beginning to tear down the CofE. These were the Puritans, a large group. Religious zeal caused them to build an army and go to war violently to “complete the Reformation,” and to establish the kingdom of Christ with a Church built on the Geneva model. I have traced their writings and manifestos from their exile in Frankfort and Geneva in 1553, when Queen Mary came to the throne, to their revolution in the next century, in which there were over 200,000 war-related deaths. The Puritan Oliver Cromwell, known as “General of the Parliament,” beheaded his king. Peaceful he was not.

But now, for Part 2 of The Story I have been researching the revolutionary Reformers, who sought from the very beginning to tear down the CofE. These were the Puritans, a large group. Religious zeal caused them to build an army and go to war violently to “complete the Reformation,” and to establish the kingdom of Christ with a Church built on the Geneva model. I have traced their writings and manifestos from their exile in Frankfort and Geneva in 1553, when Queen Mary came to the throne, to their revolution in the next century, in which there were over 200,000 war-related deaths. The Puritan Oliver Cromwell, known as “General of the Parliament,” beheaded his king. Peaceful he was not.