William Tyndale did not write much about the New Testament book of Revelation, but he used imagery from it, including imagery of the beast and the “mark of the beast.”

Chapters 13-20 in Revelation contain prophecies about a beast, or beasts, who would have power over the nations and deceive them. The Greek word is therion, which means a savage, dangerous, or venomous animal (Strong 2342). Tyndale understood the dangerous beast(s) to represent false religion, and especially, at the time he wrote, the Roman Catholic Church. For centuries the Roman Church had been a powerful and savage persecutor, and it is widely accepted to be one of the beasts that the apostle John prophesied about in Revelation. John also referred to people who would take the “mark of the beast”:

If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives his mark in his forehead or on his hand, the same shall drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is poured in the cup of his wrath.

And the beast was taken, and with him that false prophet who worked miracles before him, by which he deceived them that received the mark of the beast, and them that worshipped his image. These both were cast into a pond of fire burning with brimstone.

(Revelation 14:9-10 and 19:20, the October Testament, NMB)

Obviously, those who take the mark of the beast would have some close connection with the Roman Church (or other similar religious beast), and thus receive a mark or sign from that beast. What might that mark be? Tyndale often spoke of it as ordination into the ranks of the Roman Church; for example, as a priest or bishop, or taking vows to become a monk or friar in a monastic order.

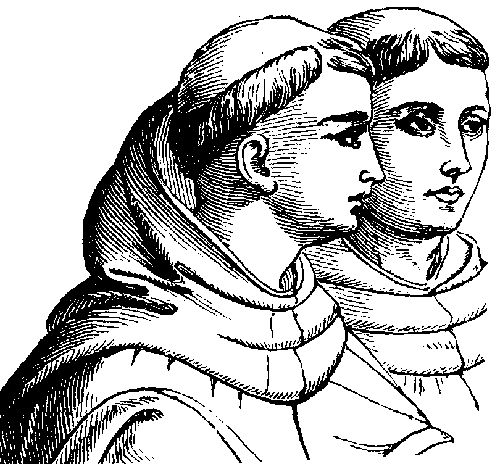

In his book The Obedience of a Christian Man, describing the gross unlawfulness of the Roman Catholic Church, Tyndale wrote,  “For if any man will obey neither father nor mother, neither lord nor master, neither king nor prince, the same needs but only to take the mark of the beast, that is, to shave himself a monk, a friar or a priest, and is then immediately free and exempted from all service and obedience due to man” (p. 36). In this quotation, Tyndale was referring in part to the exemption that, historically, was granted to Roman Catholic clergy to exempt them from prosecution for criminal acts. The result of this was that some men sought ordination in the Church to escape prosecution for their crimes. To accept ordination into the apostate Church was, therefore, to take the mark of the beast of sin and unlawfulness. Ordination into the beast meant doing the beast’s work in whatever form that might take, including preaching false doctrine, persecuting the saints, etc. What Tyndale referred to as “shaving oneself a monk” meant to shave the top part of the head bald, as in the illustration, leaving a rim of hair around the skull. This was called a tonsure. Since shaving one’s head was a symbol of belonging to monastic orders in the Roman Church, this also was to take one of the beast’s marks.

“For if any man will obey neither father nor mother, neither lord nor master, neither king nor prince, the same needs but only to take the mark of the beast, that is, to shave himself a monk, a friar or a priest, and is then immediately free and exempted from all service and obedience due to man” (p. 36). In this quotation, Tyndale was referring in part to the exemption that, historically, was granted to Roman Catholic clergy to exempt them from prosecution for criminal acts. The result of this was that some men sought ordination in the Church to escape prosecution for their crimes. To accept ordination into the apostate Church was, therefore, to take the mark of the beast of sin and unlawfulness. Ordination into the beast meant doing the beast’s work in whatever form that might take, including preaching false doctrine, persecuting the saints, etc. What Tyndale referred to as “shaving oneself a monk” meant to shave the top part of the head bald, as in the illustration, leaving a rim of hair around the skull. This was called a tonsure. Since shaving one’s head was a symbol of belonging to monastic orders in the Roman Church, this also was to take one of the beast’s marks.

Tyndale said of ministers or clergy, “If they minister their offices truly, it is a sign that Christ’s Spirit is in them, if not, that the devil is in them.” If they do not minister their offices truly, then they are “dreamers and natural beasts, without the seal of the Spirit of God, but sealed with the mark of the beast and with cankered consciences” (Obedience p. 110-11). Tyndale wrote:

Bishops and priests who preach not, or who preach anything save God’s word, are none of Christ’s nor of his anointing: but servants of the beast whose mark they bear, whose word they preach, whose law they maintain clean against God’s law. (Obedience p. 92)

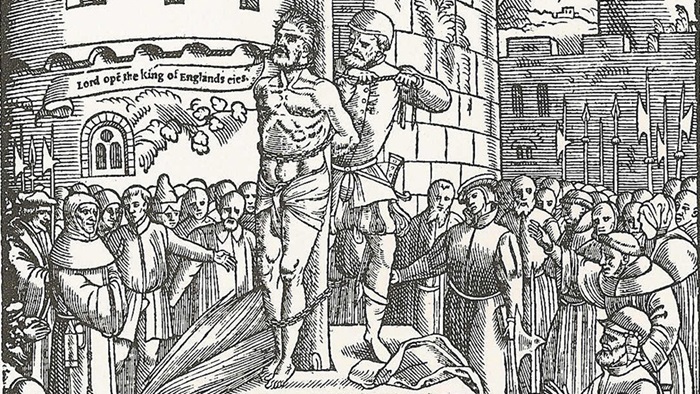

Tyndale himself was ordained a priest in the Roman Catholic Church, though the beast defrocked him, imprisoned him, publicly strangled him, and burnt his body. But a faithless man who turns himself over to the doctrine and practices of the beast, not caring about truth, and who takes part in deceiving the people, and who does not repent, has taken the beast’s mark. There are many modern so-called Christian organizations that Tyndale might identify as beasts, which, though they have lost their power to persecute, still take people captive through deception and error. But there are also savage beasts in other religions today.

Tyndale strangled before being burned in Vilvoord, in 1536.

Men (or now, women) might accept ordination from the beast in ignorance, or even as part of their search for God. Lately I have been reading the book Far from Rome, Near to God, which is the testimony of 50 converted Catholic priests. It is fascinating to read about their struggles to find truth, which often remind me of Martin Luther’s quest for truth as he broke free, step-by-step, from the strongholds of Romanism. The priests all describe their time in monasteries, which indicates that things have not changed much: isolation, asceticism, intense indoctrination with Roman dogma, praying the rosary, self-flagellation, and complete obedience to the superior of the order characterized their duties. One former priest wrote, “My blind and rebellious wanderings took me through the dark and treacherous paths of Romanism, psychology, eastern religions, and new-age philosophy.” The Lord can and does rescue his children from many a beast – which, in the end, are all the different faces of the one who roams the earth seeking whom he can devour.

Does it not make sense that receiving the mark of the beast is joining with false religion, rather than receiving a microchip under the skin as many think today? Our eternal well-being depends on receiving the true knowledge of God and avoiding the doctrine and deception of the beast, but a microchip will be of no consequence in a thousand or a million years.

Ruth Magnusson Davis, September 2020.

Quotations from The Obedience of a Christian Man are from the Penguin Classic edition, published 2000.