This blog post is my short answer to the question, was Luther antisemitic? I answer, “no.”

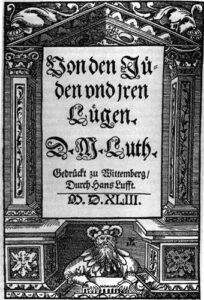

Luther has been accused of prejudice and hatred toward Jewish people, and even of inciting Nazism. These charges arise especially out of his small book, On the Jews and Their Lies, published in 1543. I will quote here some of the things he said in that book. I have also written a longer answer to the question, was Luther antisemitic, with more quotations – the worst as well as the best – in this paper, which is also linked again below.

Three main points in Luther’s defence are:

1) He rejected any form of ethnocentric prejudice, let alone hatred. He insisted that all peoples are as one, descended from the same ancestors, and that love requires impartiality. On this ground he condemned the ethnocentric prejudice of the Jews themselves. He also stated clearly that the Jews must never be personally harmed, as is discussed below.

2) Luther did, however, oppose the anti-Christian teachings and practices of Judaism.

3) Luther’s opposition to Judaism was based on a thorough knowledge of ancient and contemporary Jewish history, literature, and practice, all of which he reviewed in his book so that people would understand the reasons for his opposition and concerns.

Title page of 1543 edition of “On the Jews and Their Lies” by Martin Luther

The definition of antisemitism

The Oxford English Dictionary defines antisemitism as prejudice, hostility, or discrimination towards Jewish people on religious, cultural, or ethnic grounds. Despite appearances, this does not describe Luther’s treatment of the Jews. His quarrels with them inevitably touched on religious questions – how could they not? – but were not rooted in prejudice as the world imagines. Luther considered the Jews as he considered all people, according to how they received or rejected God’s word and gospel, which is the same thing that divides us in the eyes of the Lord (Lu. 12:51), and based on their treatment of their fellow man.

Luther expressly condemned ethnocentric prejudice

In this post, the page numbers in brackets refer to On the Jews and Their Lies as contained in volume 47 of the American edition of Luther’s Works. The page references are not exhaustive, since Luther often returned to discuss the same items several times in his book.

The truth is that Luther rejected any form of prejudice, hostility, or discrimination on ethnic grounds. This is why he condemned the Jews’ claim to divine favour on account of their race and lineage. He complained that, in their synagogues and around their dinner tables, following their religious liturgy, they regularly praised and thanked God that they were born Jews, not Gentiles. He called this carnal and arrogant. He also objected to the prayers of the men, who praised God because they were not born women. To disdain others on account of their natural attributes is to blaspheme God’s creation:

God has to endure that, in their synagogues, their prayers, songs, doctrines, and their whole life, they come and stand before him and plague him grievously (if I may speak of God in such a human fashion). Thus he must listen to their boasts and their praises to him for setting them apart from the Gentiles, for letting them be descended from the holy patriarchs, and for selecting them to be his holy and peculiar people, etc. And there is no limit and no end to this boasting about their descent and their physical birth from the fathers.

And to fill the measure of their raving, mad, and stupid folly, they boast and they thank God, in the first place because they were created as human beings and not as animals; in the second place because they are Israelites and not Goyim [Gentiles]; in the third place because they were created as males and not as females….

They have portrayed their Messiah to themselves as one who would strengthen and increase such carnal and arrogant error regarding nobility of blood and lineage. That is the same as saying that he should assist them in blaspheming God and in viewing his creatures with disdain, including the women, who are also human beings and the image of God as well as we; moreover, they are our own flesh and blood, such as mother, sister, daughter, housewives, etc. For in accordance with the aforementioned threefold song of praise, they do not hold Sarah (as a woman) to be as noble as Abraham (as a man).… But enough of this tomfoolery and trickery. (p140-42)

Luther wrote that both Gentiles and Jews “partake of one birth, one flesh and blood, [and] neither one can reproach or upbraid the other about some peculiarity without implicating himself at the same time” (p148). Further, we are all “lumped together” equally as sinners by nature and birth (ibid).

Therefore, on ethnic grounds Luther was not antisemitic and did not discriminate. But the Jews did discriminate on ethnic grounds – and the men on the grounds of gender.

Luther was not antisemitic, but he did oppose the anti-Christian teachings and practices of Judaism

To the extent that Luther’s quarrel with the Jews reached into the areas of religion and culture, it was due only to how their apostasy from God’s word manifested in these areas. It is inevitable that apostasy will manifest in religion and culture. This is true for Jew and non-Jew.

Luther learned about some of the religious issues he discussed in his book from converted Jews, including a former rabbi, Anthony Margaritha, who had written his own book to expose some very disturbing prayers and rituals of synagogue practice. I know it will shock many people to learn that these included prayers (which were later removed from the Jewish Talmud) for the stabbing and death of the Gentiles (p273). Luther rightly said such prayers were devilish and malicious. The Jews also regularly prayed for the overthrow of Germany and other nations so they could advance in dominion in the world (p264, 293, etc.), which they believed was God’s promise for them. Such goals obviously threatened national security, among other problems. (When the contents of the Talmud became more widely known to the authorities, the Jews, fearing for their own safety, expunged the worst prayers from it; however, when Luther lived they were still part of it. This is further discussed in my longer paper).

Luther also explained how, in addition to cursing their host country and the Gentiles, the Jews regularly cursed Jesus and his mother, the virgin Mary. They called Mary a whore who conceived Jesus in adultery with a blacksmith (p257). They perverted Jesus’ name in Hebrew; they shortened Yeshua to Yeshu so that it operated as a kind of secret curse that only they could understand, and they spit on the floor at the mention of this name (ibid). They called Jesus Hebel Vorik, which signified that he was the very embodiment of lying and deception (p284-85; more on this below). Further, when conversing with each other about Jesus, they said Delateatur nomen eius, which means “May God exterminate his name,” or “May all the devils take him” (p257).

The Jews also ritually cursed Christians. Luther explained,

They treat us Christians similarly in receiving us when we go to them. They pervert the words Seid Gott willkommen [literally, “Be welcome to God”] and say, Sched wil kem! which means: “Come, devil,” or “There comes a devil.” Since we are not conversant with the Hebrew, they can vent their wrath on us secretly. While we suppose that they are speaking kindly to us, they are calling down hellfire and every misfortune on our heads. (p257)

Again, Luther learned about these curses and rituals from converted Jews who were eye-witnesses to and former practitioners of them, including the former rabbi Anthony Margaritha.

The advice that has generated charges that Luther was antisemitic

On account of these “abominations,” as Luther called the rabbinic prayers and rituals, he said that if the Jews would not stop, their synagogues should be destroyed. This should be done not only for reasons of national security, but, perhaps more important to Luther, to demonstrate that Christians would not knowingly condone the public cursing of Christ. If Christians tolerated this when they had the power to prevent it, then they were participants in the abominations (p270). Luther said that, while inward belief could not be compelled, public blasphemy should be prevented if possible (p268f, 279f, etc.).

Further, Luther said that if the Jews would not reform, they should be expelled from the country and go back to Jerusalem, and their Talmuds and literature should be destroyed. He also said their homes should be burned down, which I found extreme, but then I learned that it was not a new idea: in former times, the authorities burned down the homes of serious offenders as a manifest sign and warning to others. This historical context explains Luther’s comment that the burning down of the homes of Jewish offenders was intended to “bring home to them the fact that they are not masters in our country, as they boast” (p269). Also, expulsions were then common for treason or crime. The Jews themselves had Anthony Margaritha expelled from Augsburg for writing his book – hardly a crime! (These things are further discussed in my longer paper.)

Luther emphasized repeatedly that his purpose for these measures was to ensure that the German people did not, as he wrote, “become guilty sharers before God in the lies, the blasphemy, the defamation, and the curses which the mad Jews indulge in so freely and wantonly against the person of our Lord Jesus Christ, his dear mother, all Christians, all authority, and ourselves” (p274). He had a keen sense of duty to avoid partaking in the sins of others – especially gross, persistent, open blasphemy against the Son of God:

If we permit them to do this where we are sovereign, and protect them to enable them to do so, then we are eternally damned together with them because of their sins and blasphemies, even if we in our persons are as holy as the prophets, apostles, or angels. …

They dub [Jesus] Hebel Vorik; that is, not merely a liar and a deceiver, but lying and deception itself, viler even than the devil. We Christians must not tolerate that they practice this in their public synagogues, in their books, and in their behavior, openly under our noses and within our hearing in our own country, houses, and regimes. If we do, we, together with the Jews and on their account, will lose God the Father and his dear Son, who purchased us at such cost with his holy blood, and we will be eternally lost, which God forbid.

Accordingly, it must and dare not be considered a trifling matter, but a most serious one, to seek counsel against this. (p284-85)

And so Luther advised the authorities to act forcefully to end the evil. However, he anticipated that they would not heed his advice. He wrote, “I observe and have often experienced how indulgent the perverted world is when it should be strict, and, conversely, how harsh it is when it should be merciful” (p276). Nonetheless, he said that he had spoken his mind fully and was thereby exonerated before God (p292).

But it is most important to note that Luther insisted the Jews must not be personally harmed. He wrote:

You, my dear gentleman and friends who are pastors and preachers, I wish to remind very faithfully of your official duty, so that you too may warn your parishioners [to] be on their guard against the Jews and avoid them so far as possible. They should not curse them or harm their persons, however. (p274)

Luther also never advised the authorities to harm the Jews personally, and he said no action against them should ever be taken from a spirit of vengeance (p268). Therefore, to accuse him of sowing the seeds of Nazism is absurd and slanderous. It is as facile to accuse him of fomenting Hitler’s evil as it is to blame Moses for the evils that men have wrought through misuse of the Bible.

Luther’s strong and sometimes intemperate language: Straining at gnats?

I acknowledge that Luther sometimes went far in using intemperate language in his book On the Jews and Their Lies, especially when writing about the ritual cursing. But I will leave it to God to judge if he went “too far,” as people say. When the Day of Judgement comes, we will learn the measure of God’s wrath against his servant Luther for his indignant and “vehement” speech, as well as the measure of his wrath against those who cursed his Son. I know I would rather be found on Luther’s side than on the side of those who cursed the Son. They definitely went too far.

Finally, the point should be made that Luther did not live in such a delicate age as we do; strong and unpleasant language was common in 16-century literature. The theory that illness or medication contributed to his irascibility is possible – I recall him lamenting in one of his later works that he was too often angry – but it ignores the gravity and severe provocation of the problems he was addressing. He was not wrong to be angry about them. To find fault with his language and overlook the terrible problems he was writing about is to strain at gnats and swallow a camel.

Luther’s other concerns

Luther addressed other rabbinical teachings and practices in his book, along with a fascinating and learned review of history – especially certain events of the first century, which he examined alongside messianic prophecy to show how rabbinic interpretations of history and Scripture do not add up. I learned a lot from his exposition of the prophecies in Daniel 9. He drew from a wealth of personal knowledge and study, and he possessed keen insight. After discussing the history of the Jews, their false interpretations of Scripture, their spiritual blindness, and the problems in the synagogues, he mourned:

The wrath of God has overtaken them. I am loathe to think of this, and it has not been a pleasant task for me to write this book, being obliged to resort now to anger, now to satire, in order to avert my eyes from the terrible picture which they present. It has pained me to mention their horrible blasphemy concerning our Lord and his dear mother, which we Christians are grieved to hear. I can well understand what St. Paul means in Romans 10 when he says that he is saddened as he considers them. I think that every Christian experiences this when he reflects seriously, not on the temporal misfortunes and exile which the Jews bemoan, but on the fact that they are condemned to blaspheme, curse, and vilify God himself and all that is God’s, for their eternal damnation, and that they refuse to hear and acknowledge this, but regard all of their doings as zeal for God.

Oh God, heavenly Father, relent and let your wrath over them be sufficient and come to an end, for the sake of your dear Son. Amen.

Thus Luther’s true heart and prayer for the Jewish people.

Therefore, Luther was not antisemitic, but was motivated only by his love of God’s word and Son, and his love of truth and righteousness. He was motivated by these same things in all his writings, whether against the Jews, Turks, Roman Catholics, Arians, Sacramentarians, his fellow Germans, the peasant insurrectionists, or others. This is shown in my longer paper, Luther Was Not Antisemitic. My defence there – my longer answer to the question, was Luther antisemitic? – is structured around the horrid accusations against Luther made by the Concordia House editor Franklin Sherman in his introduction to On the Jews in volume 47 of Luther’s Works.

Sherman, a pro-Judaizing ecumenist, attacked Luther’s character, knowledge, and “thought,” as well as his supposed gullibility, superstitious beliefs, stereotypes, abusiveness, and negative attitude. He said Luther possessed an “immense capacity for hatred” and provided a prototype for Hitler’s “final solution.” He also defended the “merits” of Judaism while he never spoke well of Christianity; he even refused to acknowledge salvation by faith alone, which he presented as merely Luther’s view. Quoting from rabbinical sources that he preferred far above anything Luther ever wrote, Sherman went so far as to suggest Judaism was the “mother” of an ungrateful and unappreciative Christianity. He also repeatedly referred readers to sources that blamed Christians for the circumstances of the Jews throughout the New Testament age.

Sherman’s unfortunate influence can sometimes be seen in Lutheran circles, where people echo his accusations and say they wish Luther had never written On the Jews and Their Lies. But I for one am glad he wrote his book. I learned a lot from it – about history, about prophecy, about the Talmud, and more. It was an eye-opener.

********

Ruth Magnusson Davis. Blog post May 2021, Martin Luther Was Not Antisemitic: A Defence

Link to longer defence on Academia.edu, which can read as a pdf online or downloaded and printed.

Consider also our book, The Story of the Matthew Bible, Part 2, which shows how Lutheran the 1537 Matthew Bible was. It also highlights some little-understood differences between the early Lutherans and Calvinists in the 16th century. The Geneva Bible changed some translations, but especially the notes, to advance Calvinist and puritan doctrine and practice.

********

K.Ps. Was Luther antisemitic? Was Martin Luther antisemitic? Martin Luther Was Not Antisemitic