Is it wrong to celebrate Easter because it is really an ancient pagan festival in honour of an idol named Ishtar? No. This is a myth of recent origin. In fact, there is no written record in Old or Middle English that connects Easter with Ishtar. The extant writings show that Easter was always, from the beginning of the English language, a Christian festival, and was associated with the concept of the Christian Passover.

Easter is pure to the pure

We are free to observe Easter if we so choose. What matters is that our hearts and intent be right (Ro.14:5-6). On Easter Sunday, I sing in my heart and praise God for what he has won for me through the passion and resurrection of his Son. That is what counts.

But moderns who war against Easter say it is a pagan feast in honour of a heathen goddess named Ishtar (or Astarte or Ashtoreth, other names of this alleged idol). I do not have Ishtar in my heart when I praise God for his Son, but they say that the etymology of the word ‘Easter’ proves it is pagan, because the word derives from Ishtar’s name. This is false, as I will show. But even if it were correct, it would be irrelevant, because God looks on our hearts, not on the etymology of our words. Indeed, he abhors strife about words (1 Ti. 6:4). Further, to the pure, all things are pure (Titus 1:15). Thus Easter is pure to those who are pure.

This should be enough to answer the warriors against Easter. But to engage them on their own battleground, their arguments are considered below.

The misguided war on Easter

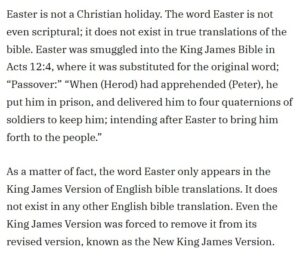

When I entered into Google the question, is it wrong to celebrate Easter? – the top result was as shown in the screenshot below[i]:

This pretty well sums up the typical, modern objections to Easter, which are made not only by the Jehovah Witnesses, but also some evangelicals. But every statement is false. Further, inside the Vanguard News article is the common allegation that Easter is Ishtar worship. It says that Noah’s son Ham married a woman called Ashtoreth, or Ishtar, which name (it asserts without evidence or references) is transliterated in English as ‘Easter.’ It goes on to say that Ashtoreth “made herself ‘the Queen of Heaven;’ the goddess of fertility, and became an object of worship.”

Since the Vanguard article was number one in the Google rankings, I will answer it here.

First, concerning the alleged “surreptitious merging” of Christianity and paganism: this appears to be a partial truth falsely presented. I have read (though I have not researched it) that under the Roman empire, perhaps partly in an attempt to help convert the pagan peoples without coercion, certain holidays (but not Easter) were observed coincidentally with theirs. This was not done with a “surreptitious” purpose to pull a fast one on the Christians and hoodwink them to convert them to paganism. The idea is absurd. However, Easter has always been observed around the time of the Jewish Passover, on the Sunday after the Paschal full moon, being the time of Jesus’ passion. It is a moveable feast based on the Old Testament feast, which was in turn based on the lunar cycle. The date varied depending on the calendar used, but there can be no question of compromise with pagan festivals.

Second, as will be seen below, the word ‘Easter’ is in fact scriptural. It existed in Bibles for centuries – and, yes, even in “true” Bibles. Especially in true Bibles.

Third, while etymology is not an exact science, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, which is the most reliable, thorough, and unbiassed authority, ‘Easter’ most likely derives from a Germanic base meaning ‘east.’

Fourth, according to the records of written English going back to the beginning, there was no association of ‘Easter’ with Ishtar, nor is there evidence of transliteration from ‘Ishtar.’

Fifth, what this and every other article that wars against Easter will not tell you, is that the real ancient meaning of ‘Easter’ was ‘Passover.’ This is why it is scriptural. The early Bibles, in both the Old and New Testaments, called the Passover ‘Easter.’ The word ‘Passover’ did not enter the English language until the 16th century. ‘Easter,’ and also the word ‘Paske’ (seen below), were used instead.

When Easter meant Passover

In past centuries, to say ‘Easter’ was the same as to say ‘Passover.’ This is difficult to imagine now because the semantics have changed so much, but, in fact, the two words were often used interchangeably. John Rogers, editor of the Matthew Bible, made this clear in one of his notes on the book of Numbers, as we will see. This semantic connection with the Passover lent meaning and significance to the word ‘Easter,’ which is now sadly lost. It could mean either the Jewish Passover, which was also called the “Jewish Easter,” or Easter as the Christian Passover, depending on the context. Also, Jesus was often called the “Easter lamb,” meaning the Passover lamb. ‘Easter’ was, therefore, a word that brought to mind the great Passover: the pure, shed blood of the precious Lamb, which saves from death and delivers from bondage.

If the semantic equivalence of Easter with Passover had not been lost, perhaps it would not be so easy now to ask, is it wrong to celebrate Easter, because that would be like asking if it is wrong for Christians to keep their Passover. How could it be wrong to remember the Lamb of God who died for us? And what place could Ishtar have in such a remembrance? None at all, of course. And she never did have any place in the Easter/Passover remembrance, as will be seen.

Easter in Bible history

A good way to understand how the ancients used the term ‘Easter’ is to see how it was previously used in the Bible. Below is how it was used in a West Saxon Gospel (c. the 6th-7th century), and also in the three Reformation Bibles,[ii] to mean ‘Passover’ in Mark 14:1. For context, I’ve shown also the King James Version below. The older quotations are in original spelling:

Mark 14:1

OE West Saxon Gospels æfter twam dagum wæron eastron.

Coverdale 1535 after two dayes was Easter.

1537 Matthew Bible After two dayes folowed ester.

1540 Great Bible After two dayes was Easter.

KJV 1611 After two days was the feast of the Passover.

See also the following, from Reformation Bible translations:

Coverdale 1535, Ezekiel 45:21 Vpon ye xiiij. daye of the first moneth ye shal kepe Easter.

Tyndale 1535, Matthew 26:18-19 My tyme is at hande; I will kepe myne ester at thy housse.

Tyndale 1535, 1 Corinthians 5:7 Christ oure esterlambe is offered up for us.

Tydnale 1535, Acts 20:6 We sayled awaye from Phillippos after the ester holydayes.

‘Passover’ can be substituted in every quotation above for ‘Easter.’ For moderns, this makes the verses meaningful, but this is only because Easter has lost its association with the Passover. Even worse, to some people, due to the war on the semantics of ‘Easter,’ the word makes them cringe. Semantics are sharp arrows in Satan’s quiver. He has used them to such effect that Tyndale’s “ester holy dayes” have become Ishtar’s unholy days.

The Scripture texts above show that the Vanguard article spoke untruly about ‘Easter’ in English Bibles. I did a computer search of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament and found that he used ‘Easter’ (or ‘ester’) twenty-eight times. Coverdale used ‘Easter’ and ‘Passover’ interchangeably in the Old Testament of his 1535 Bible, though he usually favoured ‘Passover.’

Chapter 9 of the book of Numbers in the 1537 Matthew Bible was Tyndale’s translation, and it deals with the Passover. John Rogers’ chapter summary here reads, “The Easter or Passover offering of the clean and unclean.” This shows that both words means the same. Verse 13 in chapter 9 and Rogers’ note on it, with updated spelling, were as follows:

Numbers 9:13, Tyndale/ Matthew Bible But if a man… was negligent to offer Passover, the same soul shall perish from his people, because he brought not an offering unto the Lord in its due season.

Note a: In like manner it is with us in our spiritual Easter or Passover. Whosoever does not reverently believe the redemption of mankind, which was thoroughly finished in offering the true lamb of Christ, and amends not his life, nor turns from vice to virtue in the time of this mortal life, shall not belong to the glory of the resurrection, which shall be given to the true worshipers of Christ, but shall be rooted out from the company of the saints.

Thus, with the coming of the New Covenant and the Christian Easter celebration, there was a deep, reverent, spiritual connection between the old and the new feasts. This meaning was clearly explained in the Matthew Bible, but has now been entirely lost. In place of this reverent understanding and appreciation, Easter has been virtually blasphemed by those who do not understand.

More falsehoods from warriors against Easter

The Vanguard article contained even more elaborate falsehoods about Easter in the Bible, as seen in the screenshot below:

To answer this, in the first place, the word ‘Easter’ was not “smuggled” into Acts 12:4 in the KJV, but was kept there. The KJV was based on the Bishops’ Bible, which in turn was based on the Great Bible, and both these versions used ‘Easter’ in this place:

Acts 12:4 in the 1540 Great Bible, 1568 Bishops Bible, and 1611 KJV: He put him in prison … intending after Easter to bring him forth to the people.

Therefore, ‘Easter’ was not “smuggled into” the KJV in some nonsensical plot to trick the Christians into worshipping Ishtar.

Clearly, the Vanguard statement, “the word Easter only appears in the King James Version of English Bible translations,” is false. Even the Geneva Bible (GNV) used ‘Easter.’ The GNV was produced by staunch Puritans, who were the first party to make open war on Easter.[iii] (Their war ended by outlawing Easter in 1647, after they had seized power in England.[iv]) Perhaps, therefore, keeping ‘Easter’ in their Bible was an oversight. But they used it in their chapter summary on Deuteronomy 16. Coverdale and Rogers also had ‘Easter’ here:

Chapter summaries, Deuteronomy 16

Coverdale 1535: The feast of Easter, Whitsunday, and of tabernacles.

Matthew Bible 1537: Of Easter, Whitsuntide, and the feast of tabernacles.

GNV 1560 and 1599: Of Easter. 10.Whitsuntide, 13. And the feast of tabernacles.

By keeping ‘Easter’ here, the Puritans showed that they knew their readers would understand Easter and Passover as one and the same thing. However, my search of the online version of the 1599 Geneva Bible on biblegateway.com indicated that, except in this place, the Puritans removed ‘Easter’ from the Bible.[v] My search of the KJV shows that they removed it everywhere except in Acts 12:4, and used ‘Passover’ instead. The modern Bibles that I searched do not use ‘Easter’ at all. Nor would I expect them to, since the word has now lost its connection with the Passover.

The true etymology of ‘Easter’

Etymology: The branch of linguistics which deals with determining the origin of words and the historical development of their form and meanings. (Oxford English Dictionary)

As mentioned, it is difficult to understand how the ancients understood Easter because the word has now been emptied of its association with Passover. However, it is important to grasp, partly in order to see how the modern warriors against Easter misrepresent its etymology.

To research questions about English words – their origin, historical development, and meanings – the Oxford English Dictionary online (OED) is the most thorough and dependable resource. For each word, the OED gives all the meanings in which it has ever been used. It shows only two meanings for ‘Easter,’ and both go back to Old English:

Easter (online Oxford English Dictionary):

Entry 1. The most important and oldest of the festivals of the Christian Church, commemorating the resurrection of Christ and observed annually on the Sunday which follows the first full moon after the vernal equinox. Also (more generally): Easter week or the weekend from Good Friday to Easter Monday, Eastertide.

Entry 2. = Passover. Now only in Jewish Easter or with other contextual indication.

Below, the English quotations in the screenshot from the OED show that people used ‘Easter,’ in a variety of spellings, to mean ‘Passover.’ Since only subscribers can access the online OED online, I give the information here by way of screenshot:

People might wonder why Wycliffe’s 14th century Bible is not represented in any of the Bible quotations. It is because, instead of ‘Easter,’ he used ‘pask’ or ‘paske,’ a Middle English form of the Latin pascha, which in turn is derived from the Hebrew pesach, or Passover. In the 1398 quotation, “ester’ = pascha, and in the 1450 quotation, ‘eastren’ = Paske.

We see, therefore, that from the earliest age of the English language until the 16th century, people used Eastren/eastrum/ester/pask/pascha/ etc., in the sense ‘Passover.’ Pascha has retained this meaning, but ‘Easter,’ unfortunately, has not. The word ‘Passover’ only entered the English language in the Early Modern period (i.e., in the 16th century). The OED shows the first use of ‘Passover’ in Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s Bible translations. The ancients never used it, nor could use it, since the word was unknown to them. Therefore, they used ‘Easter’ or ‘Paske’ instead.

Below is the first part of OED entry 1 under ‘Easter.’ It shows quotations from eOE (early Old English). Again, there are many variant spellings, including ‘estran,’ ‘eastron,’ Eastrena,’ ‘eastrum,’ ‘ester,’ etc. Further, though I cannot include all the quotations, I did review them, and none show ‘Easter’ used with reference to Ishtar or any other idol:

The true etymology of ‘Ishtar’

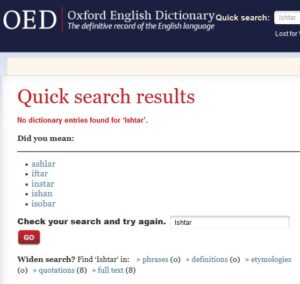

I decided to search ‘Ishtar’ to see if something was missing under the ‘Easter’ entry in the OED. Maybe, somewhere else, there might be evidence that at least some ancient peoples used ‘Easter’ in reference to Ishtar?

In the OED, information for each word includes all its variant and historical spellings. When a person searches any spelling, old or new, they will find the word. Notwithstanding, just to be sure, I searched ‘Ishtar’ in a variety of spellings, including ‘Ish’tar’ and ‘Ish-tar.’ I also searched Astarte and Ashtoreth. But there were, in fact, no entries for any of these words. However, the OED did show ‘Ishtar’ used in eight quotations. I checked these and found that they did not date from ancient times, but only from 1862 – and again, there was no evidence that ancient people used ‘Easter’ in the sense ‘Ishtar.’ Indeed, in this connection is only used by moderns who want to demonize Easter.

Below, for the record, is a screenshot of my OED search results for ‘Ishtar’:

The screenshot indicates that the OED robots found the word ‘Ishtar’ in only 8 quotations or texts. As I mentioned, the earliest of these is 1862.

The origin of ‘Easter’: A Germanic root meaning east

According to the OED, the weight of evidence is that ‘Easter’ derives from a Germanic base meaning ‘east.’ The German Ostern (formerly ostera, ostarum, etc.) and Old Dutch Oster are derived from the same base.

Some have noted that the east is important in Christian practice and traditions, and they posit a historic connection with ‘Easter.’ Following ancient tradition, many churches place their altars in the east end of the church (or in the “liturgical east” if it is not in fact facing east). When the Israelites were journeying through the wilderness, only Moses, Aaron, and Aaron’s sons, the anointed priests, were permitted to camp on the east side of the Tabernacle (Numbers 3:38). The wise men who sought the infant Jesus followed a star that they saw in the east. Some understand Matthew 24:26, which prophesies of the coming of the Son of man as lightning that comes from the east, to be a reference to the Second Coming. Revelation 7:1 speaks of the angel coming from the east having the seal of the living God; this would be a reference to Jesus. The daystar that rises in our hearts (2 Peter 1:19) rises in the east. Anglican ministers who lead their congregations in prayer, pray toward the east. Thus, symbolically considered, the east is holy; it has always had a special significance in Christian practice.

Below is a screenshot from the OED online discussing the origin of ‘Easter’:

The OED discusses one alternative theory about the origin of ‘Easter,’ which arises from a comment made by Bede. He mentioned an Anglo-Saxon goddess called ‘Eostre’ or ‘Eastre’ (not ‘Ishtar’). Feasts for this goddess were apparently held about the same time as Easter. However, the OED and most scholars discount the idea that the word ‘Easter’ is derived from the name of this goddess, as there are no records to support a connection with the development of the word ‘Easter.’ And finally, the OED did not mention ‘Ishtar’ as a possible root of ‘Easter.’

This review shows that the etymological arguments of the opponents of Easter are baseless. There is zero evidence to connect Easter with Ishtar. One wonders if any idol ever really existed under this name. However, even if she did, and even if Ishtar worship was practiced by the ancients, it is irrelevant to the history of the Christian Easter. Someone pointed me to an Encyclopedia Britannica article giving the history of Ishtar and describing her worship by ancient people, as if this disproves my conclusion. However, even if the goddess did exist of old, the fact is irrelevant because the records do not link her with Easter at all, and further, the name Ishtar has only recently been ascribed to her. The whole Ishtar-Easter connection is make-believe.

What has been lost

When the people of Tyndale’s generation, not to mention also the people of ancient times, crossed the threshold of their church doors for an Easter service, they understood it to be their Passover remembrance. The clear connection of Easter with Passover is a sad loss. Among other things, this has meant the loss of a sense of community with Christians who went before – who, with a faithful mind, celebrated Easter, as their Passover. We must not think that Tyndale, Coverdale, Cranmer, Luther, or others knew no better than to ignorantly celebrate a heathen goddess! I once read a modern writer who commented that we needed to forgive Tyndale for using ‘Easter’ in his New Testament. What division this causes, and what a dishonour to God’s faithful servant and martyr.

Conclusion: the final answer to the question, is it wrong to celebrate Easter?

The written records, going back to the earliest age of the English language, show that the word ‘Easter’ (or ester, eastron, etc.) was ONLY ever used to mean the Christian holiday and the Passover, and that it was NEVER used in any connection with Ishtar, nor with any pagan idol. Therefore we never need to ask, is it wrong to celebrate Easter, out of concern for any pagan origins or associations. The evidence against the Easter-Ishtar allegation is conclusive: it is false. It is a modern myth.

When we keep Easter/Passover/Pascha, we are simply remembering our Saviour, and how he won our exodus from our Egypt and deliverance from bondage to Satan, while we walk to the promised land. It is just as the Jews kept their Easter to remember their deliverance from bondage while they walked to the promised land. If it sounds strange to speak of the Jews keeping Easter, it only proves how much meaning the word has lost. It was not strange to our ancestors. We should put the Passover back in Easter!

Ruth Magnusson Davis, May 2022

KW: Is it wrong to celebrate Easter? The most complete answer NO to the question, is it wrong to celebrate Easter, considering the true etymology of the words ‘Easter’ and ‘Ishtar.’

___________________________________

Endnotes:

[i] This and the second screenshot of the Vanguard article were taken on April 24, 2022. I do not want to link to the article, which would only help maintain its high Google ranking.

[ii] The Reformation Bibles are Coverdale of 1535, the 1537 Matthew Bible, and the 1539-1540 Great Bible.

[iii] An open war on Easter began with the Puritans and has continued with the modern Ishtar myth. But this is not to say that there was never any kind of covert war against Easter before. That surreptitious war is by Satan, of course, who will use any means possible, covert or overt, to defeat the Christian Passover. Covertly, he robs it of the reverence it is due (as by changing semantics), loads it with superfluous, secular, or impious observances, or whatever. The true celebration and exaltation of Christ our Passover Lamb and Saviour is a feast and festival that Satan despises.

[iv] The Puritans warred on Easter from the 16th century until they finally overthrew the English king and seized control of the English parliament in the mid-17th century. Then, in an ordinance of June 8, 1647, they outlawed Easter and Christmas. When the Puritans came to America, they again outlawed these feasts by an ordinance of 1659, and people who breached the laws were imprisoned or fined. The Puritans argued that Easter was Romish and superstitious. A link to the full text of the 1647 Puritan ordinance in England is posted at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/acts-ordinances-interregnum/p954 .

[v] I searched the 1599 Geneva Bible on biblegateway.com on April 21, 2022, and found only this single use in Deuteronomy. I also manually checked several verses in the 1560 GNV and found no use of ‘Easter’ other than in Deuteronomy. I cannot confirm that ‘Easter’ was removed everywhere else from the 1560 version, but it is likely.

The early Puritans made many changes to the Bible based on sometimes radical ideology. Some of the most significant and little-known changes are reviewed in The Story of the Matthew Bible: Part 2, The Scriptures Then and Now.

________________

Is It Wrong to Celebrate Easter? Copyright Ruth Magnusson Davis, May 2022. Permission granted to use short quotations for reviews or for information, with credit. Contact for other permissions concerning Is It Wrong to Celebrate Easter?