Researched and Prepared by Ruth Magnusson Davis

Also answers the question, What is the abomination of desolation standing in the holy place?

This short post is the first in the series “Principal Matters from the 1537 Matthew Bible.” The purpose of the series is:

(1) To get to know the Table of Principal Matters in the Matthew Bible.

(2) To learn through Bible studies from the Reformation.

“As the bees diligently do gather together sweet flowers, to make by natural craft the sweet honey, so have I done with the principal topics contained in the Bible.”

So began John Rogers’ introduction to the Table of Principal Matters in the 1537 Matthew Bible. The Table was a concordance at the front of the book. It set out Bible topics in alphabetical order. Under each topic were statements of doctrine with scripture references for further study. This series proceeds topic by topic following the order of the Table and sets out the scriptures cited, taken from the Matthew Bible. Where typographical errors in the Table prevented me from locating the correct verses, I showed the citation as written (e.g., Exodus viii.f.)

The introduction to the Principal Matters series provides important information to get the most out of the topics.

Topic: Abomination

“Abomination” is the first topic in John Rogers’ Table of Principal Matters in the Matthew Bible. Of special interest is point (6), concerning the abomination of desolation standing in the holy place. This abomination was mysterious in Matthew and Mark, but Luke says what it was in his Gospel. However, many have failed to see the link between Matthew, Mark, and Luke. This study made it clear.

Now, from the Matthew Bible:

Abomination

(1) Abominable before God are idols and images before whom the people bow themselves.

Deuteronomy 7:25-26 The images of their gods [the gods of the nations] you shall burn with fire. And see that you covet not the silver or gold that is on them, nor take it to yourselves, lest you be snared therewith.a Bring not therefore the abomination into your house, lest you be a damned thingb as it is. But utterly destroy it and abhor it, for it is a thing that must be destroyed.

Note a: Whatever gold or silver, or honour or profit, calls away from the word of God belongs to the images of their gods, and must therefore be abhorred; yea, even if they are good works, when you think that you do them of your own strength and not helped by God.

Note b: or cursed thing.

Deuteronomy 27:15 Cursed is he that makes any carved image or image of metal (an abomination to the Lord, the work of the hands of the craftsman), and puts it in a secret place.

(2) That man is an abomination who forsakes the true God to serve idols, and who despises the truth for profane doctrines.

Isaiah 41:29 Lo, wicked are they, and vain, with the things also that they take in hand; yea, wind are they, and emptiness, together with their images.

(3) We ought not to follow the abominations of the Gentiles.

Leviticus 18:30 Therefore, see that you keep my ordinances and follow none of these abominable customs that were practised before you, so that you do not defile yourselves through them. For I am the Lord your God.

(Citation not identified: Exodus viii.f.)

(4) That which men esteem to be excellent is abominable before God. Luke 16:15.

(5) The transgressors of God’s commandments are abominable.

Leviticus 26:14-17, 23-24, 30 14But if you will not hearken to me nor will do all these my commandments, 15or if you despise my ordinances, or if your souls refuse my laws, so that you will not do all my commandments but break my decree, 16then I will do this to you: I will visit you with vexations, swelling, and fevers that will destroy your eyes, and with sorrows of heart. And you will sow your seed in vain, for your enemies will eat it.

17And I will set my face against you … 23And if for all this you will not yet learn, but walk contrary to me, 24then I will also walk contrary to you, and will punish you yet seven times for your sins. … 30And I will destroy your altars built upon high hills, and overthrow your images, and cast your bodies on the bodies of your idols; and my soul will abhor you.

(6) The abomination standing in the holy place is Jerusalem besieged by her enemies.

Matthew 24:15-16 When you therefore see the abomination that betokens desolation spoken of by Daniel the prophet stand in the holy place, let him who reads it, understand it. Then let those who are in Judea flee into the mountains.

Mark 13:14 Moreover, when you see the abomination that betokens desolation, of which Daniel the prophet has spoken, standing where it ought not, let him who reads, understand. Then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains.

Luke 21:20-21 And when you see Jerusalem besieged with a host, then understand that its desolation is near. Then let the people who are in Judea flee to the mountains, and let those who are in the city get out.

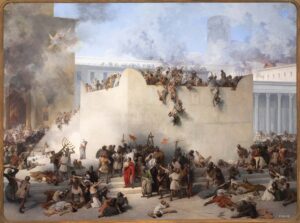

Roman armies beseige Jerusalem in 70 AD. The abomination of desolation standing in the holy place had come, and would cause the desolation of the holy city and temple.

‘Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem’ is a painting by F. Hayez. It depicts the desolation of the second temple by Roman soldiers in 70 AD.

Notices:

– New Testament Scriptures are from the October Testament, the New Testament of the New Matthew Bible. The Old Testament Scriptures and Apocryphal writings are taken directly from the Matthew Bible, with obsolete English gently updated.

– Click here for Information about the New Matthew Bible Project, our project to gently update the 1537 Matthew Bible.

– Sample scriptures from the New Matthew Bible are here.

KW abomination of desolation standing in the holy place