The teaching of William Tyndale on Antichrist is scattered throughout his writings, but the most succinct was this passage from Parable of the Wicked Mammon:

Mark this also above all things – that Antichrist is not an outward thing, that is to say, a man that should suddenly appear with wonders, as our fathers talked of him. No, verily; for Antichrist is a spiritual thing. And is as much to say as Against-Christ; that is, one that preacheth false doctrine, contrary to Christ.

Antichrist was in the Old Testament, and fought with the prophets. He was also in the time of Christ and the apostles, as thou readest in the epistles of John, and of Paul to the Corinthians and Galatians, and other epistles. Antichrist is now, and shall, I doubt not, endure till the world’s end. But his nature is (when he is revealed and overcome with the word of God) to go out of play for a season, and to disguise himself, and then to come in again with a new name and new raiment. As thou seest how Christ rebuketh the scribes and the Pharisees in the gospel (who were very Antichrists), saying, “Woe be to you, Pharisees, for ye rob widows’ houses; ye pray long prayers under a colour; ye shut up the kingdom of heaven, and do not allow those who would to enter in; ye have taken away the key of knowledge; ye make men break God’s commandments with your traditions [precepts]; ye beguile the people with hypocrisy,” and such like. Which things all our prelates do, but have yet gotten themselves new names and other garments, and are otherwise disguised.

There is a difference in the names between a pope, a cardinal, a bishop, and so forth, and to say a scribe, a Pharisee, an elder and so forth; but the thing is all one. Even so now, when we have exposed him, he will change himself once more, and turn himself into an angel of light.[1]

Four points may be taken from the teaching of William Tyndale on Antichrist:

(1) Antichrist is a spiritual thing.

Antichrist is an evil spirit, the spirit of Satan, Christ’s adversary. Therefore, Antichrist is not a particular man, though he is personified in false teachers, and particularly in pre-eminent ones. Tyndale and other Reformers often referred to the pope as Antichrist, and in the quotation above, Tyndale called the Pharisees “very Antichrists.”

(2) Antichrist is now. The spirit works wherever and whenever he can through false teachers.

The work of Antichrist is always the same: to preach against the doctrine of Christ. In related writings, Tyndale elaborated that Antichrist suppresses the sacraments, and that he seeks authority and pre-eminence in the Church. He is also a persecutor. These are the things that Antichrist does.

It was obviously important in the teaching of William Tyndale on Antichrist to dispel the false idea that he was a future man. If we believe this, we will miss Antichrist now: we will be asleep, not watching, not even believing that he might presently be among us as a false teacher or prophet. Tyndale warned:

That Against-Christ or Antichrist that shall come is nothing but such false prophets as shall juggle with the Scripture and beguile the people with false interpretations, as all the false prophets, scribes, and Pharisees did in the Old Testament.[2]

John Rogers echoed William Tyndale on Antichrist in his note on 1 John 4 in the Matthew Bible:

Antichrist signifieth not any particular man, which (as the people dream) should come in the end of the world. For ye see that even in St. John’s time he was already come. But all who teach false doctrine contrary to the word of God are Antichrists.

(3) Antichrist goes out of play and then comes in again.

There are seasons when Antichrist has greater or lesser power. In his preface to the New Testament, Tyndale wrote that as it had gone under the Old Covenant, so would it go under the New: Antichrist would have seasons of power when the light of God’s word would be darkened. Before the Reformation, Antichrist had been entrenched in power in the Roman Catholic Church for a long time. Tyndale prophesied that after the Reformation, he would return. This brings us to the fourth point.

(4) Antichrist was bound to come on the heels of the Reformation in a new disguise.

Tyndale foresaw that after Antichrist had been exposed in the Roman Church and people had the Bible in their own languages, he would disguise himself with new names and garb, pose as an angel of light with appearances of righteousness, and begin again to darken the word and truth of God. This has occurred through various means. It has come to pass that the pure word has been almost destroyed in some of the worst modern Bibles, and many modern churches or denominations are completely apostate.[3] This is the very work of Antichrist, the false angel of light, who is gaining power as modern apostasy grows. Indeed, Antichrist is now revealed in this apostasy, for those who have eyes to see.

For a in-depth (10 pages) examination of Tyndale’s teaching about Antichrist and his translation of 2 Thessalonians 2, see Tyndale’s Doctrine of Antichrist. This paper compares Tyndale’s teaching with other views prominent today or in the past, including the Orthodox Church’s teaching, Puritan teaching from the 16th-17th century, and modern evangelical beliefs.

RMD, Feb 2021

___________________

[1] William Tyndale, Parable of the Wicked Mammon, (Facsimile; no pl.: Benediction Books), 4-5. (Updated: ‘suffer’ to ‘allow’ with syntax, ‘uttered’ to ‘revealed’ and ‘exposed,’ ‘which’ to ‘who,’ ‘them’ to ‘themselves,’ ‘senior’ to ‘elder.’)

[2] Tyndale, The Obedience of a Christian Man, ed. David Daniell (London: Penguin Books, 2000), 17.

[3] Modern Bible versions, along with the history of translation of 2 Thessalonians 2 on Antichrist from the revisions in the Geneva Bible onward, are reviewed in chapter 23 of The Story of the Matthew Bible, Part 2, our new release. Here is a link to buy it on Amazon USA

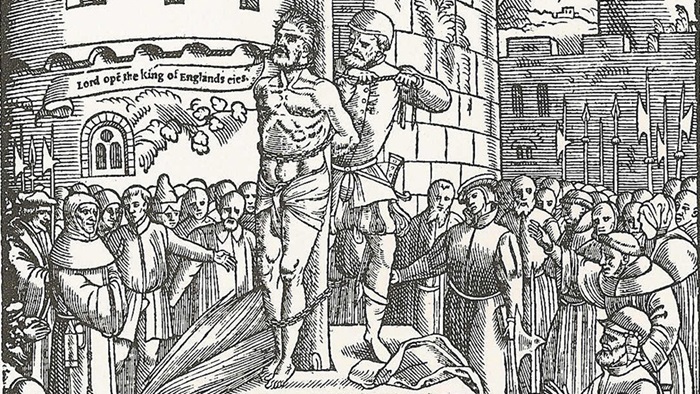

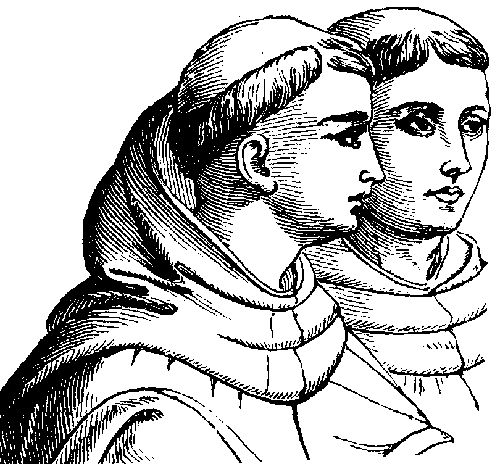

“For if any man will obey neither father nor mother, neither lord nor master, neither king nor prince, the same needs but only to take the mark of the beast, that is, to shave himself a monk, a friar or a priest, and is then immediately free and exempted from all service and obedience due to man” (p. 36). In this quotation, Tyndale was referring in part to the exemption that, historically, was granted to Roman Catholic clergy to exempt them from prosecution for criminal acts. The result of this was that some men sought ordination in the Church to escape prosecution for their crimes. To accept ordination into the apostate Church was, therefore, to take the mark of the beast of sin and unlawfulness. Ordination into the beast meant doing the beast’s work in whatever form that might take, including preaching false doctrine, persecuting the saints, etc. What Tyndale referred to as “shaving oneself a monk” meant to shave the top part of the head bald, as in the illustration, leaving a rim of hair around the skull. This was called a tonsure. Since shaving one’s head was a symbol of belonging to monastic orders in the Roman Church, this also was to take one of the beast’s marks.

“For if any man will obey neither father nor mother, neither lord nor master, neither king nor prince, the same needs but only to take the mark of the beast, that is, to shave himself a monk, a friar or a priest, and is then immediately free and exempted from all service and obedience due to man” (p. 36). In this quotation, Tyndale was referring in part to the exemption that, historically, was granted to Roman Catholic clergy to exempt them from prosecution for criminal acts. The result of this was that some men sought ordination in the Church to escape prosecution for their crimes. To accept ordination into the apostate Church was, therefore, to take the mark of the beast of sin and unlawfulness. Ordination into the beast meant doing the beast’s work in whatever form that might take, including preaching false doctrine, persecuting the saints, etc. What Tyndale referred to as “shaving oneself a monk” meant to shave the top part of the head bald, as in the illustration, leaving a rim of hair around the skull. This was called a tonsure. Since shaving one’s head was a symbol of belonging to monastic orders in the Roman Church, this also was to take one of the beast’s marks.